Friday, October 30, 2020

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers | Ear, Nose and Throat Disorders...

Lupine Publishers | Lasers & Pedodontics

Lupine Publishers | Journal of Pediatric Dentistry

Introduction

The medical terms such as magical and lightening quick are used to represent lasers [1]. Theodore H. Maiman in 1960 coined the term laser, which was initially termed as maser which stands for “microwave amplification by stimulated emission of radiation”. However, the term LASER is an acronym for light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation [2,3]. Three types of lasers used for surgical therapy in the oral cavity are neodymium lasers - YAG (Nd: YAG), of argon (Ar) and carbon dioxide (CO2) [3]. Lasers have largely replaced scalpels and other instruments in the field of medicine because of its advantages [4-6]. Different laser wavelengths have different absorption coefficients wherein laser energy can be absorbed or transmitted based on the structure of the target tissue. The presence of water, which is an essential component of all biologic tissues, is important for the use of lasers [2,6]. For hard tissues, Er lasers are used whereas any laser can be used for soft tissue components [2,6,7].

Applications of Lasers in Pediatric Dentistry

For caries removal

Erbium group of lasers are preferred for deep enamel, dentin, and caries removal, whereas the Nd: YAG laser is designated for superficial pigmented caries removal. The other advantages being the non-requirement of anesthesia and the use of conventional drills, which cause micro-fracture of tooth during preparation [1,2]. During cavity preparation, after the removal of enamel, the settings are adjusted to reduce the energy levels as dentin is less mineralized and has higher water content than enamel [2].

Removal of restorations (including amalgam)

Lasers should never be directed towards amalgam and should be pointed towards the surrounding enamel to create a small trough, and hand instruments are used to elevate the restoration out and later the cavity preparation is completed. Also, other restorations like composite and glass ionomer can be removed/replaced [1,2].

Preventive treatment

At the early stages after tooth eruption, enamel grooves are the site of early caries. This can be treated using lasers by cleaning, sterilizing and restoring the same. Also, many studies have reported that etched enamel by erbium has properties like the acid-etched enamel [2].

Treatment of peri coronal problems in erupting teeth

Lasers are used in non-contact mode to remove the pericoronal tissue covering the newly erupted tooth, which might help in relieving any discomfort, swelling, or infection in the tissue overlying the emerging tooth [2,9].

Gingival re-contouring and orthodontic purposes

Excess gingival growth by the use drugs or by poor oral hygiene, and during other surgical procedures including orthodontics requires removal of tissue in some cases. This can be accomplished by the use of lasers which can be done without the need for a local anesthesia. Use of topical anesthetic can be supplemented for the treatment procedures [8].

Treatment of ankyloglossia

Tongue is stabilized with a hemostat and the frenum is revised, while avoiding any damage to the glands on the floor of the mouth [8].

Treatment of aphthous ulcers and herpetic lesions

Use of low power settings with the laser energy directed at the target tissue in the non-contact mode, for a duration of 15-30 second intervals for three to four times, helps in pain relief. The use of laser in the initial stages in herpes labialis may prevent its further progression and provide a palliative effect for the area and prevent its progression [2,8].

Pulp therapy

The ability of laser to close the dentinal tubules and provide a sedative effect on pulpitis has somewhat encouraged the use of laser in indirect pulp capping [8]. Also, the use of lasers to sterilize the canals and also create a hemostatic environment in adjunct to the conventional procedures has created a stir for the use of lasers.

Other surgical procedures

Other surgical procedures like apicectomies and amputation of impacted teeth underneath the bone also can be performed with the use of lasers. The erbium lasers are ideal for these surgeries and a variety of tips, settings and water sprays can be used. Softtissue ablation does not require water spray whereas removal of bone needs to be done with water [2,9].

Advantages of laser therapy

a) Decreasing inflammation and pain.

b) Reduced healing period [3,4,9].

c) Good & faster healing properties.

d) Reduced chances of infection.

e) Reduced bleeding.

f) Instant hemostatic achievement.

g) Good margins.

h) Patients apprehensive for blade.

Contraindication of Laser Therapy

a) Patients with pacemakers, however it can be used with precautions in some case [9].

b) Patients who are sensible to light.

c) In epileptic patients.

d) In patients with antecedent of arrhythmia or chest pain.

e) Avoided on tumorous tissues or benign tumors with malignant potential.

Conclusion

Natural light is and has been considered as the curator [10]. Lasers have gained tremendously over the years; its advantages far outweigh its disadvantages. However, there still exists some limitations as well as some contraindications, which stop its usage with the cost factor being one of it. Nevertheless, it would be the future instrument of choice for most of the procedures included in all the fields with surgery, periodontics, endodontics and orthodontics being one of them.

Read

More Lupine

Publishers Pediatric Dentistry Journal Articles:

https://lupine-publishers-pediatric-dentistry.blogspot.com/

Wednesday, October 28, 2020

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers | Onion (Allium cepa) Production...

Friday, October 23, 2020

Lupine Publishers | Bilateral Dens in Dente in Maxillary Laterals: A Case Report

Lupine Publishers | Journal of Pediatric Dentistry

Abstract

Dens invaginates is a defect categorized by a prominent lingual cusp and centrally located fossa. It occurs due to early invagination of the enamel epithelium into dental papilla of the underlying tooth germ. The affected teeth show a deep invagination of enamel as well as dentin initiating from foramen caecum or tip of the cusps and may extend even into the root. The teeth that are most frequently involved teeth are the maxillary lateral incisors, there might also occur a bilateral involvement. In this anomaly there can be seen several morphologic variations and it may lead to early pulpal involvement from the caries progressing into the pulp from lingual pit. The treatment varies from a preventive restoration to endodontic therapy, depending on the severity of the case. The present case report refers to one such case having a deep lingual pit bilaterally in both the maxillary permanent lateral incisors.

Introduction

Dens invaginatus is a rare malformation of teeth, showing various morphological variations. Radiographically the teeth show an invagination of enamel and dentin extending up to the pulp cavity or the roots. This malformation was described earliest by Ploquet [1], who discovered this anomaly in a whale’s tooth [2]. Dens invaginatus in a human tooth was first described by a dentist Socrates’ in 1856 [3]. ‘Anomalous cavities in human teeth were reported by Mühlreiter [4] in 1873, Baume [5] in 1874 and Busch [6] in 1897 reported about this anomaly as well. In 1887 Tomes [7] described the dens invaginatus as: The enamel of the coronal portion is generally well developed but we tend to find a small depression in its centre that appears to be a dark spot. On division of the tooth longitudinally, there occurs a dark centre of depression that is a blocked orifice within the tooth. If the section be a fortunate one, we shall be able to trace the enamel as it is continued from the exterior of the tooth through the opening into the cavity, the surface of which is lined completely with this tissue’ [7]. There are various reports on cases of dens invaginatus malformation in the dental literature [8-11]. Synonyms for this anomaly include:

a) Dens in dente,

b) Invaginated odontome,

c) Dilated gestant odontome,

d) Dilated composite odontome,

e) Tooth inclusion,

f) Dentoid in0 dente.

Case Report

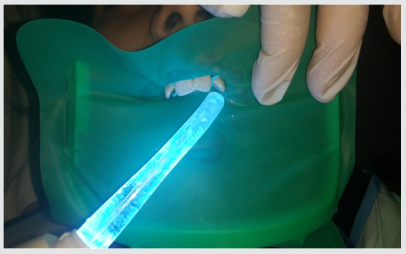

A 12-year-old female patient referred to the Pedodontics department with the complaint of irregularly arranged teeth. General health of the patient was normal and medical history was not relevant. Clinical examination revealed teeth 12 and 22 with a lingual pit. The pre-operative photographs were taken for the same (Figure 1). An intraoral Periapical radiograph was also taken for both the teeth, which revealed deep lingual pits involving the coronal part of teeth (Figure 2). As the teeth showed only incisal invaginations, and no pulpal involvement preventive treatment was selected. Also, if the pits were left untreated, it would harbor irritants and microorganisms further leading to caries. And as these pits were deep enough, the caries would progress rapidly into the pulp and cause pulpal infection leading to the need for endodontic treatments.

Treatment Done

Following the oral prophylaxis, rubber dam placement was done for 12 and 22 (Figure 3). The teeth were initially washed, cleaned and dried. After that acid etching was performed using 37% phosphoric acid for 20 seconds. It was then washed and dried. Following that dentin bonding agent was applied with the applicator tip and cured for 20 seconds. The pits were then restored with flowable composite bilaterally (Figure 4). The teeth were then examined for any excess material and later finishing was done. The occlusion was also checked for any interference followed by post-operative photographs (Figure 5). Furthermore, the child was referred for orthodontic consultation.

Discussion

Dens Invaginatus has several variations of it. Oehlers gave a classification for various types of dens invaginatus [12]:

a) Type I: an enamel-lined minor form occurring within the confines of the crown not extending beyond the amelocemental junction.

b) Type II: an enamel-lined form which invades the root but remains confined as a blind sac. It may or may not communicate with the dental pulp.

c) Type III: a form which penetrates through the root perforating at the apical area showing a ‘second foramen’ in the apical or in the periodontal area. There is no immediate communication with the pulp. The invagination may be completely lined by enamel, but frequently cementum will be found lining the invagination.

Prevalence of Dens Invaginatus

The teeth mainly affected are maxillary lateral incisors and bilateral occurrence is not rare, they occur in almost 43% of all cases [13]. Swanson & McCarthy (1947) were the foremost to present bilateral dens invaginatus malformation, Conklin (1968) presented a patient with both maxillary central and lateral incisors affected bilaterally, and Burton et al. (1980) reported a case with six teeth involved, the maxillary incisors as well as the maxillary canines. Krolls (1969) also detected dental invaginations in maxillary central incisors and in many maxillary and mandibular premolars in a single patient. Conklin (1978) found the malformation in four mandibular incisors in one patient. There are many theories described in the literature to explain about the dental coronal invaginations some of them being:

a) The bulking of the enamel organ was thought to be caused due to the growth pressure of the arches [14,15].

b) Focal failure of the growth of the inner enamel epithelium leads to the invaginations; however, the surrounding epithelium continues to grow and engulfs the static area [11].

c) The invagination is due to the aggressive proliferation of a part of the inner enamel epithelium invading the dental papilla. It was thought as a ‘benign neoplasm of limited growth [16].

d) Protrusion and distortion of the enamel organ is thought to cause an enamel lined channel terminating at the cingulum or at the incisal tip. This might also lead to an irregular crown formation [17,18].

e) The ‘twin-theory’ [18] suggested a fusion of two toothgerms to be the causative factor.

f) Infection was also considered to be responsible for the anomaly [19].

g) Trauma was thought to be a reason, but they could not adequately explain why just maxillary lateral incisors were affected and not central incisors [20].

h) Most authors consider dens invaginatus as a deep folding of the foramen coecum during tooth development which may even result in a second apical foramen [3].

i) On the other hand, the invagination also may start from the incisal edge of the tooth. Genetic factors cannot be expelled (Grahnen 1962, Casamassimo et al. 1978, Ireland et al. 1987, Hosey & Bedi 1996).

Clinical Features

Due to the invagination there is just a thin layer of enamel and dentin left, which thus allows several microbes into the pulpal space easily. In some of the cases there is a complete enamel lining present. Also, channels may be present between the invagination and the pulp chamber. Pulp necrosis hence occurs in the earlier stages, within a few years of eruption and may be even before the root closure. The sequelae of untreated coronal invaginations can be as follows:

a) Abscess formation.

b) Retention of neighboring teeth.

c) Displacement of teeth.

d) Cysts, or Internal resorption.

Treatment Modalities

Preventive and restorative treatment should be opted for teeth with deep palatal or incisal invaginations and should be treated by fissure sealing [21]. Also, composite resin restoration followed by pit and fissure sealant can be done in the required cases [21]. Root canal treatment, surgical treatment and extraction of teeth should be done in severe cases wherein there is radicular invagination and pulpal involvement.

Conclusion

The clinician should be aware of occurrence of such tooth anomalies and should do a thorough clinical diagnosis as these anomalies are not rare. Earlier diagnosis and treatment of such cases can prevent further complications such as endodontic therapies and extractions. Hence the needed treatment should be done as early as possible and a periodic follow up should be maintained.

Read More Lupine Publishers

Pediatric Dentistry Journal Articles:

https://lupine-publishers-pediatric-dentistry.blogspot.com/

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers | Injuries to Ear Ossicles

Friday, October 16, 2020

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers | Bilateral Dens in Dente in Max...

Lupine Publishers | Board Certification in Pediatric Dentistry: Once it Represented the Pursuit of Excellence

Lupine Publishers | Journal of Pediatric Dentistry

Abstract

The scope and changes to the examination format for Board Certification by the American Board of Pediatric Dentistry has successfully achieved the goal of enticing and attracting significantly greater numbers of AAPD members to pursue and complete the board process. Unlike earlier times (prior to 2002), when only 15% of its membership secured Diplomate status, changes in the examination format that reduced the process from four extensive and demanding components to two much abbreviated elements, approximately 80% of its membership has now pursued and achieved certification. For better or worse, standards have been radically modified from that of elite and prestigious to that of minimally acceptable. Movement in the direction of making the examination process more attractive and simplified has become the rule rather than the exception. The bar has been sufficiently lowered by the nature of the examination changes. In so doing the demand and requirements for pursuit of knowledge has diminished. A priority for expanded membership at a significant cost has overshadowed the pursuit of excellence among the masses. The old school of thought envisioned inherent motivations to continually seek excellence and the most comprehensive level of knowledge. Its opposing school determined that inclusion of those unwilling or unable to master the highest level of competency remained deserving of recognition. Among the dilemma created by this shift in priorities is that once one fractionates the degree of difficulty and challenge to a lesser level, it is unlikely the direction can be reversed any time soon.

Introduction

What it once meant to achieve Diplomate status from the American Board of Pediatric Dentistry appears no longer to be what it once represented. In the early 1980’s approximately 15% of the membership of the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry sought and achieved this prestigious credential. Those achieving this lofty accolade were generally recognized as among the best and brightest in the field. Aspirations to secure Diplomate status were essentially limited to those with the broadest range of knowledge and commitment to excellence and lifelong learning. For whatever reasons, it became apparent that the rigorous nature of the existing four part format remained a deterrent for many to pursue Diplomate status. It became clear that examination format changes represented the only course of action for the board to increase its membership. During the following decade or so, changes in the perception of what this credential represented underwent an evolutionary change foreign to what purists think of today as a movement in an upward direction. The compass appears to have deviated in the direction of lowering rather thana raising of standards, let alone the pursuit of excellence. This was not limited to pediatric dentistry; rather instead, most medical and dental disciplines acknowledged that there was a greater need to secure and encourage larger numbers of their constituents to demonstrate this credential. In so doing, practicality and economics dictated that the ultimate attraction to accomplish this objective was that certification examinations must be abbreviated, and the bar lowered as needed to include rather than limit greater numbers from achieving certification.

Amidst the rationale for change included the fact that hospital bylaws in the late 1980’s began adopting the position that if a specialty had an American Board, that its members would need to demonstrate certification at the time of re-appointment. Significance for pediatric dentists was their ability to make use of hospital operating rooms for general anesthesia. For those unwilling to pursue board certification, the use of itinerant anesthesiologists and free-standing surgical centers was and has become an alternative, without consequences of not having achieved board certification. Nevertheless, until the format of the examination was reduced, from a rigorous four part process to a significantly abbreviated two part format, the gross numbers electing to pursue certification was not increased. To demonstrate that a significant portion of its members pursued Diplomate status, the ABPD was compelled to re-examine its criteria for certification. Perceptions of its existing degree of difficulty, time commitment, and ultimate outcome gave rise to recognition that without a substantial revision in format, increase in those pursuing certifications was unlikely. Revisions of the four part examination to an abbreviated two part exam became inevitable in not only pediatric dentistry but included orthodontics and other specialty areas. In doing so, a complete renovation in thinking took hold in that redefinition of standards was needed to permit increasing numbers to qualify as diplomates within their field. The pursuit of excellence gave way to what constituted for some, mediocrity or minimally adequate. Frank recognition that requirements for current day certification markedly differ from those of before goes largely unacknowledged. Historically, the original format comprised an all-day written examination, generated from a defined list of 200 carefully selected and identified classical as well as contemporary articles spanning all areas of pediatric dentistry. Each multiple choice question was referenced to a specific article. Successful completion of this preliminary component granted eligibility to participate in Section 2 (a no holds barred one hour oral examination before two examiners). Section 3 consisted of the submission of 5-6 specific types of cases treated which included detailed and meticulous write-ups, pre- and post-treatment radiographic evaluation, with follow-up care to demonstrate diagnostic, technical skill and clinician judgment. Upon successful completion, applicants qualified for part 4 an all-day clinical site visit in which any aspect of clinical care and practice was evaluated by two examiners, in one’s clinical or academic setting.

Effective in 2001, the four section format was reduced to two sections. Part one consisted of a half-day multiple choice written examination, based on an unidentified list of texts and papers from the literature. Satisfactory completion permitted candidates to pursue section 2 which served as a 1 1/2 hr clinical simulation on a small range, in essence replacing sections 2,3 and 4. During this period, for one year, till 2002, candidates had the option of choosing between the four part format and the abbreviated two part formats. In recognition that the new format constituted an abbreviated revision, concerns emerged with respect to a potential need for development of a Re-Certification component within a ten year span. Over the next decade, consistent with the concept of Re-Certification developed by the ABPD and other disciplines, a protocol with intent to demonstrate a propensity for Diplomates to continue to manifest a course of lifelong learning resulted in the formulation of a 50 question, open-book multiple choice recertification examination mandatory for those having passed the two part format (granted limited Diplomate status every ten years). 80% correct responses were needed to pass. Unlimited Diplomates (those having completed the more rigorous four part format) today remain exempt or voluntarily excused from recertification unless they chose to participate in any capacity related to examination development or appointment to the board.

Differences in Qualification for those having completed the more comprehensive examination format

At present, there is no distinction amongst which format was undertaken and Diplomate status rewarded other than the subtlety of limited vs unlimited status and a requirement for Re-Certification for those with limited status. Questions remain whether the fifty question open book multiple choice re-certification exam constitutes a valid comparison between examination formats. An argument might be made that individuals who subjected themselves to the four part format possess a sufficient commitment to lifelong learning and keep abreast of new and changing literature. If this premise is accepted, would it not be appropriate to provide distinction in Diplomate status in some recognizable way. The AAPD has reviewed and re-assessed the granting of Fellowship status in the last few years and as such, might consider re-assigning qualification acknowledgment of differential levels of Diplomate status.

For those having completed the four part format, the pursuit of excellence applies; from the perspective of the shortened format, adequacy is implied. The two accolades are distinctly different from one another, granting equal recognition however, seems rather inappropriate. In the course of the past decade, this author has interviewed numerous board certified candidates in search of both academic and private practice positions. Query of knowledge and competency across many fundamental areas of pediatric dentistry including pediatric medicine, recognition and management of medical emergencies, simplified as well as sophisticated sedation techniques, thorough understanding of transitional dentition analysis, cephalometric and orthodontic diagnosis and mechanics, and clinical experience can often at best be described as weak. It should not be surprising that a significantly abbreviated certification process does not possess the latitude to include some or all of these areas in detail. Helpful to analysis of the merit of the different schools of thought along with respective format changes, the ABPD might seek to secure a survey of its the membership who have experienced both sides of the examination format. Similarly, it may wish to explore perceptions of the value and validation of the current Re-Certification requirement that impacts on candidates who have completed the contemporary reduced examination format. A survey to accomplish such is currently underway by this author.

Summary

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers | Impact of Insomnia on Optimism...

Wednesday, October 14, 2020

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers| The Left Common Carotid Artery ...

Friday, October 9, 2020

Lupine Publishers | Oral Squamous Papilloma on the Tongue of a 12-Year Old Female: Report of a Case with Human Papilloma Virus Literature Review

Lupine Publishers | Journal of Pediatric Dentistry

Abstract

Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection that causes squamous papilloma is common in the oral cavity of adults but not in children. Although benign, the slow progressive growth is a concern to clinicians and parents as the lesion may clinically appear as an exophytic verrucous carcinoma or squamous carcinoma. This case report describes a squamous papilloma arising on the tongue of a 12-year old child.

Keywords:Child; Human Papillomavirus (HPV); Squamous Papilloma; Oncogenic Potential; Tongue; Koilocytes

Introduction

Human papillomavirus (HPV) are slow, benign proliferations of stratified squamous epithelium frequently observed in the oral cavity that are the viral etiologic agent for squamous papilloma [1,2]. Squamous papillomata are commonly observed in adults 30-50 years of age and is the fourth most common oral mucosal lesion in both children and adults [3]. Although the entire oral cavity may be affected, the viral lesion has a predilection for the laryngotracheobronchial complex in children and the lower lip, hard and soft palate of the maxilla and uvula in adults [1,4-6]. Clinically, the lesion appears as an exophytic mass and may cause anxiety to the clinician and parents, as the lesion can clinically appear like an exophytic verrucous carcinoma, squamous carcinoma or condyloma accuminatum [1,4,7,8]. This case report describes a squamous papilloma arising on the tongue of a 12-year old child.

Virology

The human papillomavirus is a 55nm non-enveloped icosahedral double-stranded deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) virus that is a member of the papovavirus group [7-14]. There are over 150 genotypically different types and classified as either mucosal or cutaneous.10-12 The viral types with oncogenic potential include HPVs 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 55, 56, 58, 59, 66 and 68. Oral squamous papilloma infection is associated with HPV subtypes 6, 11 and 16 [7-13]. Papillomas induced by HPV types 6 and 11 are considered to have low oncogenic potential. However, approximately 85% of dysplastic lesions, carcinoma in situ and squamous cell carcinoma involve the DNA sequence of HPV 16 and 18. DNA replication of HPV occurs in the nuclei of epithelial cells. The HPV capsid proteins enter the host cell delivering the viral DNA to the nucleus which allows proliferation of the viral lesion [7,10,11,12,14].

Case Report

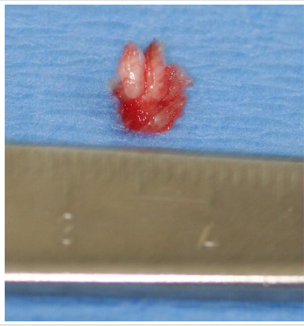

A 12-year old Asian female was referred to the office by her family dentist for evaluation of a soft tissue lesion localized to the dorsal surface of the tongue (Figure 1). The patient stated that the lesion has been present for at least six months. Her past medical history was unremarkable. She was not taking any medications and denied any allergy to medications. The patient also denies being sexually active. Sexual abuse was also ruled-out. Head and neck examination were negative for palpable neck masses and lymphadenopathy. Oral examination of the dorsal surface of the tongue revealed a pink-white colored exophytic lesion that was freely movable. The surface texture had a pebbly appearance that resembled, “cauliflower”. The remaining oral examination was unremarkable. Examination of the upper and lower extremities was negative for any soft tissue lesions resembling HPV. Based on the clinical appearance of the lesion, the differential diagnosis included squamous papilloma, verruciform xanthoma, papillary hyperplasia and condyloma accuminatum of the tongue. The father and patient were informed of the clinical findings and excisional biopsy (Figure 2) for a definitive microscopic diagnosis under local anesthesia was recommended.

Figure 1: Clinical photograph of squamous papilloma on left dorsal surface of the tongue in 12-year old Asian child.

Figure 2: Excised squamous papilloma specimen from dorsal surface of tongue of 12-year old Asian patient.

Histopathology

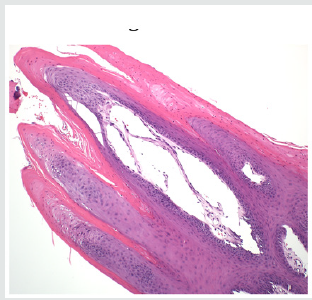

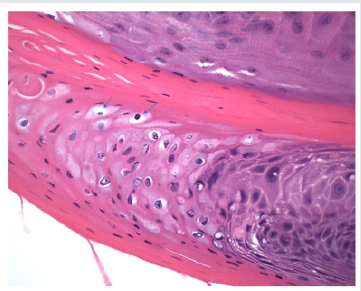

Excisional biopsy was completed under local anesthesia with 1.0mm margins of normal tissue and to the depth of the tongue musculature. The lesion was stained with hematoxylin and eosin for histopathological diagnosis. Histological examination demonstrated long, thin papillary projections of parakeratinized stratified squamous epithelium (Figure 3a). Localized areas of basilar hyperplasia with koilocytes were observed (Figure 3b). The histological findings were consistent with squamous papilloma.

Figure 3(a): Histopathology demonstrating proliferation of hyper keratinized stratified squamous epithelium finger-like projections with thin fibrovascular connective tissue core (Hematoxylin and eosin stain. Original magnification x 40).

Figure 3(b): Presence of koilocytes (arrows) in the spinous layer of the epithelium that are characteristic histopathologic findings of oral squamous papilloma (Hematoxylin and eosin stain, x 200).

Discussion

In children, viral transmission remains controversial. HPV transmission may occur by any number of different mechanisms, such as autoinoculation, heteroinoculation, perinatal transmission, sexual abuse and contact with fomites [1,4,5,9,10]. However, trauma is one mechanism that should be considered in our patient. Iatrogenic tongue biting may initiate an infection of the basal squamous epithelial cells that allows the entrance of the HPV into the tongue. Viral DNA then enters the nucleus of the infected epithelial stem cells and can replicate causing the HPV infection [15]. Histopathologic features of oral squamous papilloma demonstrate hyperkeratosis in the epithelium, proliferation of the spinous cells that result in long, thin finger-like projections above the mucosa [1- 3,8,14]. The characteristic feature of HPV infection is the presence of koilocytes (Figure 3b) which are virus-infected epithelial cells due to perinuclear cytoplasmic vacuolization of cells of the spinous layer of the epithelium. This results in the nuclei becoming pyknotic and cremated surrounded by an optically clear zone [1-10]. All the described histopathologic findings in our patient are characteristic of HPV infection. Although the prevalence of oral HPV infection is low, a bimodal distribution is observed. The highest prevalence is observed in children less than 1 year of age and the second peak occurs in adolescents, between 13 to 20 years old [9,16]. Despite the bimodal distribution, oral HPV infection is considered low in children [17]. In a study of 4140 children between the ages of 10 to 18 years old, the prevalence of oral HPV infection was 1% and the most common type was HPV 11 [18]. Treatment of HPV is by surgical excision [19]. The United States Food and Drug Administration (2016) approved Gardasil 9 human papillomavirus 9-valent vaccine to prevent infection against HPV types 6, 11, 16 and 18 (Merck & Co., North Wales, Pa). At present, only Gardasil 9 human papillomavirus 9-valent vaccine recombinant has been approved for vaccination in the United States (Center for Disease Control, 2019) [20]. To obtain the greatest clinical efficacy and cost effectiveness of vaccination, the Center for Disease Control (CDC) recommends that both male and female children between the ages of 11-12 years get two HPV vaccinations six months apart before individuals have been exposed to the human papillomavirus. It is also recommended that adult women up to age 26 years and men up to age 21 years also obtain the HPV vaccine [21].

Conclusion

A case of oral squamous papilloma on the tongue of a 12-year old female is presented to create awareness of this soft tissue lesion in the oral cavity of children due to the human papillomavirus. It is only after educating clinicians and parents about the HPV will we observe greater identification, management and treatment in the HPV infected child.

To Know More About Lupine Publishers Pinterest Click on Below Link: https://www.pinterest.com/lupineonlinegroup/

980 nm Diode Laser: A Good Choice for the Treatment of Pyogenic Granuloma

Abstract Pyogenic granuloma is a benign non/neo plastic mococutanous lesion . It is a reactional response to constant minor trauma and ca...