Objective: The purpose of this study is to deepen the description of aggressive periodontitis in developmental age patients

going through pathogenesis, epidemiology, diagnosis, treatment and differential diagnosis.

Methods: The database searching was performed on PubMed and Scopus using the following keywords: “prepubertal

periodontitis, aggressive periodontitis, periodontitis in children, periodontal disease in children and adolescents, early-onset

periodontitis”. Both clinical, laboratorial and review studies were taken into consideration.

Results: Aggressive periodontitis affects a low percentage of

children, and in those patients. Actinomycetemcomitans is the

main bacterium identified in affected sites. Moreover, it has been found

that Genetics plays a fundamental role in development and

progression, which is important to distinguish the various oral

manifestations excluding the possibility that they are a consequence

of systemic pathologies. Although it mainly affects young patients, the

treatment does not differ from that applied in adult subjects

and it consists of a causal therapy, a mechanic and a pharmacological

one, in particular the antibiotics associated with professional

hygiene has shown very satisfactory results.

Discussion: Given the great variability of oral manifestation

symptoms, there is no specific criterion for defining a high-risk

group at prepubertal age, further research is needed to identify a

robust set of genetic, microbiological and host factors markers

that may facilitate the diagnosis of the disease.

Keywords: Aggressive periodontitis; periodontal disease; developmental age; differential diagnosis

Introduction

Periodontal disease is one of the most widespread diseases in

the world and is, as a prevalence, immediately after diseases such

as diabetes and hypertension [1]. Its clinical aspects have long been

analyzed since it constitutes a worldwide problem. The pathology

affects subjects of every race, sex and age and also some risk factors

are needed in addition to the individual susceptibility for it to

develop. Even today there are not enough scientific certainties to

establish the behavior of periodontal disease in the age group that

affects children and young adults. In any case, we proceeded through

a search in the literature with the attempt to deepen its clinical

aspects, etiology, diagnosis, predisposing factors and treatment.

Periodontal diseases, despite being widespread especially in the

adult population, are not so rare even among young people [2]. For

example, gingivitis affects over 70% of children over the age of seven

[3]. Bimstein in 1991 underlined the importance of prevention,

early diagnosis and treatment of periodontal diseases in children

and adolescents because they have a high severity and prevalence

[4] and furthermore, the oral-dental incipient pathologies on small

subjects can develop into periodontal diseases in adults. However,

the degree of extension and destruction of periodontitis also

responds to a personal predisposition to the disease. The severity

index of periodontal disease can also be mediated by the presence

of some systemic diseases such as hypophosphatasia or leukocyte

deposition deficiency [5].

According to Lamster IB and Pagan M, the metabolic syndrome

(MetS) that is a spectrum of conditions that include dysglycemia,

visceral obesity, atherogenic dyslipidemia (high triglycerides and low

levels of high-density lipoprotein) and hypertension are associated

with periodontal disease. They believe that this relationship is the

result of systemic oxidative stress and an exuberant inflammatory

response. Evidence suggests that periodontal therapy may reduce

serum levels of inflammatory mediators so periodontitis treatment

could become part of the metabolic syndrome therapy [6]. Among

the various types of periodontitis, one of the less studied ones

is aggressive periodontitis. The manifestations of aggressive

periodontitis in young people have many controversial sides

and consequently, the present study proposes to look for some

clarifications regarding the aspects of the pathology

Methods

For this narrative review, the database searching was

performed on PubMed and Scopus using the following keywords:

“prepubertal periodontitis, aggressive periodontitis, periodontitis

in children, periodontal disease in children and adolescents,

early-onset periodontitis”, the investigation then focused on

evaluating the specific aspects of aggressive periodontitis in

children, consequently the following words have been introduced:

“epidemiology, classification, progression, treatment, diagnosis”.

Clinical and laboratorial studies were taken into consideration as

well as literature reviews. The last database search was performed

in September 2019.

Discussion

Aggressive periodontitis

Aggressive periodontitis can occur in several forms that is

linked to a few dental sites or in a generalized sense. The first form

usually affects smaller subjects and is connected to lesions of the

first molars or incisors or both in the presence of little plaque and

tartar, and the second form concerns post-puberty subjects with

more permanent teeth. Very often, if left untreated, the localized

forms evolve into general forms with the risk of a total compromise

of the dental apparatus. Sometimes the signs of inflammation

are not so easily detectable, which is why a child or teenager on

the first visit should always be subjected to a more in-depth

analysis by using probes to detect probing depth and radiological

investigations. There are some mechanisms that regulate

evolution in the various age groups, and the different anatomies

and physiologies can modify the development of periodontitis. In

particular, there are many structural inequalities between adults

and children. The gingiva in the young is more vascularized, has

less connective tissue around the deciduous teeth, the epithelium

is thinner and less keratinized, characteristics that can expose to

less defense to attacks bacterial. It can be said that a child, due

to its thinness of tissues, is more exposed to risk and moreover a

greater vascularization allows an easier transit of inflammation

mediators and bacteria [7]. The typical signs that indicate the

presence of a problem and that should alarm the parents are

bleeding gums during home hygiene practices, swelling, halitosis

accompanied by any recessions. Evidence shows that periodontal

disease may increase during adolescence due to lack of motivation

to practice oral hygiene but also due to changes related to puberty.

Hormones such as progesterone, estrogen and testosterone cause

greater blood circulation, greater sensitivity and greater response

to any irritation, the gengiva are often red and swollen. Hormones

are molecules with specific regulatory abilities and have powerful

effects on the main determinants of development and on the

integrity of the skeletal cavity including periodontal tissues [8].

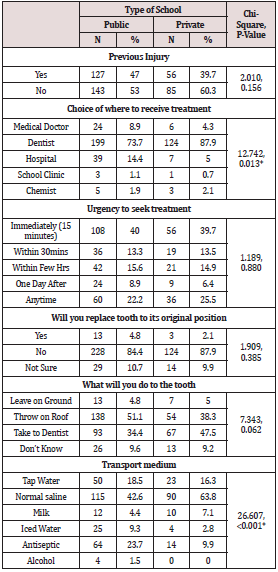

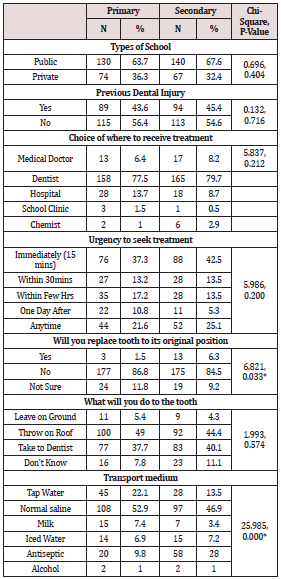

Epidemiology

A 1987 study by Sweeney [9] evaluated alveolar bone loss

around primary teeth in a population of 2,264 children. Nineteen

patients (0.84%) showed periodontal bone destruction around

one or more primary teeth; in 2 of these patients, periodontal

disease was previously identified during clinical examinations.

The microbiological study also revealed a high prevalence of

Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans and Capnocytophaga.

Another study carried out by Bimstein [10] in 1994 verified

the prevalence of alveolar bone loss in a group of 317 5-yearold

New Zealand children. The results identified that there was

a questionable bone compromise in 8.5% of the children and a

defined bone loss of 2.1%. Darby et al in 2005 studied bone loss in

542 children aged between 5 and 12 years. Reading the patient’s

radiographs, each interdental site was evaluated as: no bone loss

and therefore distance from the amelite-cementitious junction

to the alveolar ridge of less than 2 mm, questionable bone loss

i.e. distance greater than 2 mm but less than 3 mm and bone loss

defined or distance greater than or equal to 3 mm.

The results showed that 61 (13%) children presented sites

with definite bone loss, 60 children had only a questionable bone

loss, 50 children had only a defined bone loss and 21 children had

both lesions. It was also found that children of Asian-Far Eastern

origin had a higher percentage of sites with bone loss than children

of Caucasian origin, 29.5% and 19.7%, respectively, but lower than

that of children of Middle Eastern origin (35.2%). In conclusion, the

present study showed that in the population studied, 26% had bone

loss but 13% had more severe and defined lesions [11]. The studies

described above thus show that the prevalence of periodontal

disease and in particular bone loss varies from 0.84% to 13%,

but in reality, the heterogeneity of such research and the lack of

standardization makes it clear how the results are discordant and

the prevalence remains mostly dubious.

Microbiology

There are some bacteria that mainly cause periodontal disease,

and these can be transmitted within the family where the contact

between subjects is very close; through the mother’s saliva, for

example, children may be exposed to risk. Much attention has been

paid to Actinomycetemcomitans as a species implicated in the

etiology of aggressive periodontitis. Its main virulence factor is a

leukotoxin capable of eliminating important cells of the immune

system. Genetic analyses have identified a population structure of

the clonal-type bacterium with evolutionary families corresponding

to serotypes. A particular highly leukototoxic clone (JP2) of

serotype b was discovered. Its characteristics are unique in fact that

its increased leukototoxic activity is given by a deletion of 530

bases in the operon. The geographical mapping of the JP2 clone has

revealed that its colonization mainly concerns individuals of African

origin [12]. A study conducted by Burgess et al. in 2017 showed

the prevalence of the highly leukotoxic JP2 sequence compared to

the non-JP2 sequence of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans

within a group of 180 young African Americans aged between 5 and

25 years with and without localized aggressive periodontitis (LAP).

Subgingival plaque was collected from diseased sites, i.e. from

areas with probing depth greater than or equal to 5 mm that

presented bleeding and from healthy sites, i.e. from areas with

probing depth less than or equal to 3 mm that did not present

bleeding. Overall, 90 subjects (50%) tested positive for the JP2

sequence, 50 subjects (83.33%) with aggressive periodontitis

presented the sequence detected in 45 (75%) sick sites and 34

(56.67%) healthy sites [13]. Actinomycetemcomitans in general is

considered an opportunistic pathogen of the oral microbiome, in

fact many clonal types of the bacterium different from JP2 can be

isolated from healthy subjects, however, patients who present the

JP2 strain always show periodontal disease, so an etiological agent

is important for aggressive periodontitis in children, adolescents

and adults. In conclusion, there is a high risk for the development of

the disease in individuals colonized by the JP2 clone, furthermore

its transmission, as for other clonal types, occurs vertically by

close contact between people, indicating that subjects of the same

family may experience extrinsic routes of the subpopulation of the

bacterium [12].

Genetics

Genetics plays an important role in the appearance and

severity of the disease, so if a person is diagnosed with aggressive

periodontitis, it is also good to investigate the other members of

the family in order to cure or prevent their appearance. A 1994

study by Mary L Marazita studied evidence of autosomal dominant

inheritance and specific heterogeneity in aggressive periodontitis.

Analyses were conducted on 100 families, and 104 subjects were

diagnosed with aggressive periodontitis. Heterogeneity tests were

used to compare the parameter estimates and the conclusions

obtained in the black and non-black families. The results of the

segregation analysis have verified that an autosomal dominant

locus is sufficient to explain the patterns of disease transmission

to the whole family. In conclusion, in the present study, we saw

how the disease has a chance of appearing in the same branch of

descent at 70% [13]. Family aggregation of aggressive periodontitis

is not an unusual discovery. The conditions of development of

this pathology can be more complex than simple Mendelian

syndromes. Genetic studies indicate that there are several genetic

variants expressing different forms of aggressive periodontitis, but

currently it is not clear how many genes may be involved in these

non-syndromic forms of disease [14]. It is important to remember

that family models can also indicate exposure to common

environmental factors within the same family. Therefore, the

behavioral components shared by the same parental group must

also be considered: education, socioeconomic status, oral hygiene,

possible transmission of bacteria, diseases such as diabetes and environmental characteristics such as even passive smoking

influence the susceptibility of the subject as risk factors. Another

decisive reason for determining whether individuals develop

periodontitis appears to be regulated by the way they respond

to their microflora. Genetic factors also in this case modulate

the way in which individuals interact with many environmental

agents, including biofilm. The mutual influence of genetic and

environmental factors, and not only of genes, determines the result,

lifestyle factors open the way to the development of aggressive

disease [15].

Treatment

When a child is diagnosed with aggressive periodontitis, prompt

action must be taken to achieve maximum reduction of periodontal

microorganisms with the aim of blocking the development of a

more severe clinical picture. The treatment of aggressive disease

in children and adolescents does not differ from the techniques

applied to adults, in fact the etiology is always known to be bacterial

regardless of age group. The treatment therefore should be based

on the elimination of pathogens by professional hygiene, but, in

reality, in these forms of periodontal disease given the high toxicity

of the microorganisms, a systemic therapy with antibiotics must

be associated to resolve the picture. The goal is to create a clinical

condition that favors the maintenance of the greatest number of

teeth for as long as possible. The initial phase of active treatment

consists of mechanical cleaning, performed with or without the use

of antimicrobial drugs.

The downsizing and smoothing of the roots have proved

effective in improving the clinical indices, but they do not always

guarantee long-term stability, which is why systemic antibiotics as

adjuvants for radicular treatment are to be administered during

therapy, and they are more effective than root resizing alone with

the additional application of local or antiseptic antibiotics [16].

A 2005 study by Guerrero et al. evaluated the systemic

administration of amoxicillin and metronidazole in non-surgical

therapy for the treatment of generalized aggressive periodontitis.

Forty-one systemically healthy subjects in whom the disease

was diagnosed were selected. Patients received non-surgical

treatment over a 24-hour period and one half received a course

of systemic antibiotic consisting of 500 mg of amoxicillin and 500

mg of metronidazole three times a day for 7 days while the other

group of subjects received placebo. After two and six months, they

were re-evaluated and the results were as follows: in patients on

antibiotic therapy in the 7 mm pockets there was a gain of 1.4 mm

and a recovery of bone equal to 1 mm in addition to the areas with

depths greater than or equal to 5 mm had a probing less than or

equal to 4 mm. Twenty five percent of sites in test patients had a

successful improvement in clinical attack, whereas for patients

treated only with placebo, the percentage of improved sites was

16% [17]. Another study by Kaner shows how the subgingival

application of chlorhexidine via a controlled release device

(CHX chip) does not improve the clinical outcome in generalized

aggressive periodontitis. The purpose of that study is to compare

whether the additional positioning of the CHX chip is as effective as

the use of systemic antibiotics. A total of 36 patients were

diagnosed with aggressive periodontitis, one half was treated only

with slow-release chlorhexidine and the other half treated with

systemic antibiotic therapy. The subjects were re-evaluated 3 and

6 months after therapy, and it was shown that the level of clinical

attack, bleeding and probing depth had a significant improvement

in patients receiving amoxicillin and metronidaziol compared to

patients treated with the local application of antiseptics [18]. An

alternative method for the decontamination of periodontal sites

has been studied: photodynamic therapy. To reduce the excessive

use of antibiotics, new disinfection strategies have been sought.

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) or light-activated disinfection (LAD)

was first tested by Oscar Raab in the early 1900s.

For years it was abandoned due to the use of antibiotics, but it

has found a new application in the last decades both in the medical

field and in the dental field. The photodynamic reaction takes

advantage of the use of a photosensitizer (PS) and a light source

calibrated to specific wavelengths in the presence of oxygen. It

acts specifically against both Gram + and Gram- microorganisms

without causing any damage to the host cells. The toluidine blue is

very effective active against many bacteria including those involved

in periodontal disease. One example is Arweiler’s [19] research

in which the use of antibacterial photodynamic therapy (aPDT)

was studied in addition to mechanical scaling and root planning

therapy. The aim of that study was to evaluate the results following

non-surgical periodontal therapy and additional use of aPDT or

amoxicillin and metronidazole (AB) in patients with aggressive

periodontitis. Out of 36 patients treated with antibiotic therapy or

with two episodes of post-treatment photodynamic therapy, the

results after six months were the following: the probing depth was

found to be significantly reduced in both groups.

Despite this, the administration of amoxicillin and metronidazole

produced higher improvements than the existence of photodynamic

therapy, the number of pockets ≥7 mm was reduced from 141 to 3

after AB and from 137 to 45 after aPDT. Although both treatments

led to statistically significant clinical improvements, AB showed a

reduction in probing depth and a lower number of pockets ≥7 mm

compared to aPDT. In conclusion, photodynamic therapy associated

with the non-surgical periodontal therapy, despite giving favorable

results, cannot be considered a definitive alternative to the systemic

use of amoxicillin and metronidazole [20]. However, antibiotics

must be administered during or after mechanical therapy since

micro-organisms are particularly protected by biofilm in the

subgingival plaque. With regard to surgical treatment in patients

with aggressive periodontitis, it has been shown that it gives results

comparable to non-surgical treatment provided that correct oral

hygiene is maintained, that a rigorous maintenance program is

followed and that risk factors are kept under editable control [18].

Differential diagnosis

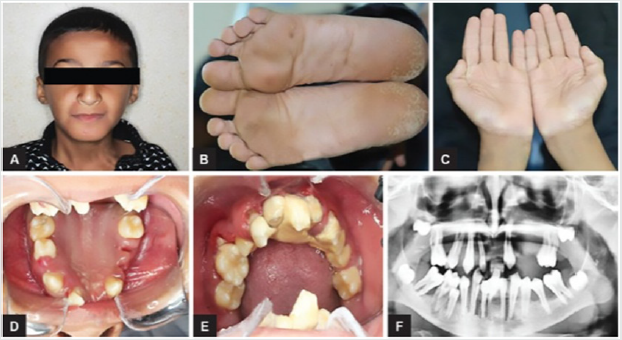

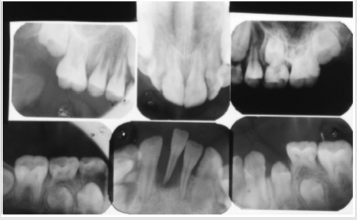

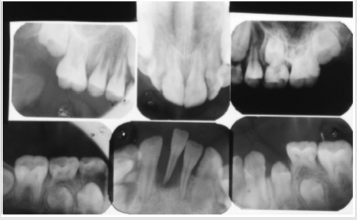

Figure 1:

Periodontal disease is characterized by the imbalance between

pathogens and host defenses leading to an inflammatory reaction

around dental tissues. To diagnose aggressive periodontitis, it

is necessary to investigate the health status of the subject and

exclude the coexistence of systemic diseases. Some disorders

can cause oral lesions clinically similar to those of aggressive

periodontitis, but it is of fundamental importance to distinguish the

various manifestations to make a correct diagnosis and intervene

with the most appropriate treatment. Examples of significant

conditions are AIDS, leukemia, diabetes or rare genetic disorders

such as histiocytosis X and Papillon-Lefevre syndrome. The latter

is a rare autosomal recessive disorder caused by mutations in the

gene that codes for cathepsin C (dipeptidyl-peptidase I inhibitor).

The syndrome is characterized by hyperkeratosis, destructive

periodontitis that occurs from childhood, recurrent piogenic and

systemic skin infections, susceptibility to bacterial infections and

intra-cranial calcifications [21] (Figures 1&2). The prevalence is

estimated to be between 1 / 250,000 and 1 / 1,000,000 subjects and is manifested in all ethnic groups. These dermatological

features appear between the first year of life and 4 years and

are accompanied by intraoral lesions that include gingival

inflammation, mobility of the dental elements, even spontaneous

bleeding and destruction of the periodontium. Patients with this

syndrome show serious signs in the oral cavity until complete

loss of deciduous bone, generating the normal appearance of the

gum. However, with the eruption of permanent teeth, the form

of aggressive periodontitis reappears. Any non-surgical but also

surgical treatment is vain and almost always leads to partial or

complete edentulism in the patient. The treatment is based on

the intake of oral retinoids, which attenuate the palmoplantar

keratoderma and slow down the lysis of the alveolar bone, and the

skin lesions can also be treated with emollients in order to hydrate

the affected area. Furthermore, good oral hygiene control, the use

of mouthwashes and even antibiotics are recommended to slow

the progression of periodontitis. Deciduous teeth or elements with

excessive mobility must be extracted and eventually replaced by

implants when the subject has completed growth.

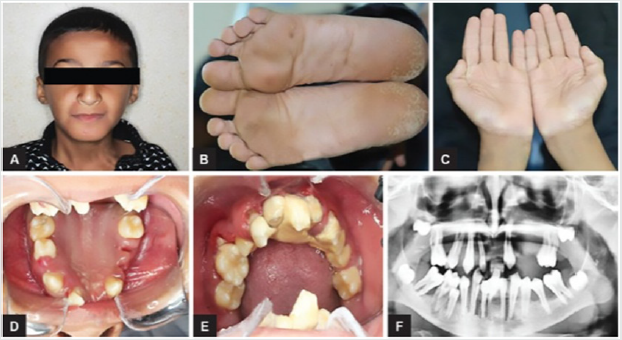

Figure 2:

The identification of the syndrome at an early age is something

multidisciplinary that can improve the patients’ prognosis [22].

Leukemia is a malignant neoplastic disease of white blood cells and

very often strikes in the pediatric age giving oral manifestations

prior to systemic onset [23]. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL or

ALL), specifically, develops when a cell destined to give rise to cells

of the immune system turns into a tumor and starts to multiply in

an uncontrolled way. Many studies show that acute lymphoblastic

leukemia is the most frequent tumor in children, representing

75% of all newly diagnosed leukemias and 25% of all childhood

malignancies [23]. The typical symptoms that characterize

lymphoblastic leukemia are fatigue, dyspnea, fever, pallor and

weight loss. Patients with this form of leukemia in the oral cavity

have pale mucous membranes and an important gingival bleeding

accompanied by lymphadenopathy in the head and neck region.

It has been shown that sometimes the initial sign of the disease

may correspond to a pericoronitis associated with a prolonged

contraction of the masticatory muscles. Numerous studies have

also reported a greater incidence of abnormalities in the oral cavity

such as the presence of large, irregularly shaped ulcers, halitosis

and a loose mucosa [24].

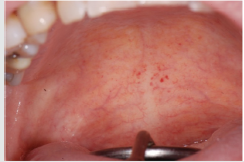

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a disease that originates

from the bone marrow. The disease is more common in adults

over 60 years and infrequent before the age of 45. Patients with

AML have symptoms related to complications related to anemia,

neutropenia and thrombocytopenia, including weakness and

easy fatigue, infections of varying severity, gingival bleeding,

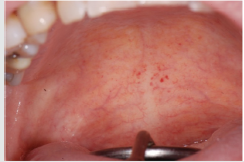

ecchymosis, epistaxis [25]. The oral examination can show pallor

of the mucosa (Figure 3), ulcerations (Figure 4), spontaneous

bleeding and bleeding (Figure 5) petechiae on gums, palate (Figure

6), tongue or lips, gingival hyperplasia (Figure 7) caused from

leukemic infiltration. Usually the lesions of the oral cavity are the

first manifestations of the disease, in particular, gingival swelling

represents 5% of the early complications [26]. In leukemic patients,

regardless of the form of the disease, oral manifestations occur as

initial evidence or of its recurrence. Symptoms mainly include gum

enlargement and bleeding, oral ulceration, petechiae, mucosal

pallor and oral infections. These lesions may be the result of

direct infiltration of leukemic cells or altered granulocyte function

[26]. With regard to oral hygiene, patients must undergo periodic

checkups and deplaquing or scaling sessions to reduce the level

of inflammation of the mucous membranes, local antiseptics or

antibiotics can be combined with active infections. Chemotherapy,

often used in the treatment of leukemia, also has consequences on

the subject that also affect the oral cavity. Often patients in therapy

are predisposed to the appearance of ulcers, lesions, infections and

are prone to have a partial xerostomia favoring plaque buildup.

Figure 3

Figure 4:

Figure 5:

Figure 6:

Figure 7:

Scurvy is another disease that manifests itself with abundant

gingival bleeding and which can be confused with aggressive

periodontitis. The primary cause of scurvy is the insufficient intake

of vitamin C mainly due to dietary imbalances. Childhood scurvy

generally appears between the sixth and twelfth year of life. The

child is easily irritated without appetite and fatigued. Sufferers of

this disease develop anemia, weakness, fatigue, edema in some

parts of the body, muscle pain in the lower limbs and ulceration of

the gums (Figure 8) [27]. It occurs later as follicular hyperkeratosis

and haemorrhage of the lower limbs, as well as bleeding in other

areas such as the gingiva and joints [28]. If the disease is not treated

it is potentially lethal due to important bleeding that can occur in the

intracranial area or, due to the poor ability of the subject to heal due

to open wound infections. At the oral level, the disease manifests

itself in widespread hypertrophic areas of the violet-colored

mucosa, a tendency for bleeding and the formation of hematomas.

In small subjects, the symptoms that appear first are the pain and

swelling of the joints accompanied by gingival hypertrophy [29].

Figure 8:

Patients suffering from this pathology are administered

quantities of vitamin C orally or through injections and, in a short

time , all symptoms disappear [28] (Figure 9). Diabetes mellitus is a

disease that can present in the oral cavity as aggressive periodontitis

and be confused with this. It includes a group of chronic metabolic

disorders that turn out to be an altered glucose tolerance or an

altered metabolism of lipids and carbohydrates [30]. It has been

shown by numerous researches that in diabetic children with

poor metabolic control, there is a greater tendency for gingivitis [30].

In fact, the high levels of glucose in the blood cause changes

in microcirculation, promote bacterial proliferation and interact

with the response of the host. Hyperglycemia caused by diabetes

mellitus alters the immune system and the increased availability of

glucose in the oral cavity environment increases the proliferation

of periodontopathic bacteria and causes marked oral inflammation

(Figure 10). In patients with diabetes, a microangiopathy occurs

and this change in the periodontium reduces the functions of

the polymorphonuclear cells, the chemotaxis, the adherence, the

phagocytosis, the use of oxygen and the elimination of antigens, thus

favoring the progression of periodontal disease. Hyperglycemia

also reduces the solubility of collagen, reduces the production of

fibroblasts and causes an increase in the levels of pro-inflammatory

mediators responsible for the destruction of connective tissues.

Changes to collagen metabolism result in accelerated degradation

of both non-mineralized connective tissue and mineralized bone.

Figure 9:

Figure 10:

Even the saliva undergoes both qualitative and quantitative

changes. Often in subjects with diabetes, the salivary flow

is reduced leading to a further development of the bacterial

species [31]. In diabetic patients, periodontal disease develops

at a younger age than the healthy population and periodontal

impairment usually occurs in adolescence but sometimes earlier

in children with diabetes [32]. In the oral cavity, there is therefore

an edematous and very inflamed gingiva, bleeding when the probe

passes and bone resorption can occur especially in cases of poor

metabolic control (Figure 11) [33], but in patients with a good

diet with good glycemic supervision and good oral hygiene, do not show

evident alteration in the mucosa (Figures 12&13). There is

then a relationship between higher levels of plaque and a higher

incidence of gingivitis in children with diabetes, moreover, the

differences in oral microflora and the impact of metabolic control

of diabetes on periodontal health have indicated a higher risk of

periodontitis in children with type 1 diabetes [34]. In conclusion,

when you are confronted with a child who has an oral situation of

persistent inflammation, you need to perform more specific tests

to understand if it is periodontitis as a manifestation of systemic

pathology or aggressive periodontitis itself. The dentist or hygienist

is usually the first to diagnose some diseases due to the involvement

of the periodontium, and it is important to have multidisciplinary

management to try to minimize the physical, psychological and

social effects of the patient at an early age.

Figure 11:

Figure 12:

Figure 13:

Conclusion

In conclusion, the review of the literature shows that

periodontal disease does not only affect adults but, even if less

frequently, it also involves children and adolescents. The forms of

aggressive disease show a family aggregation, cause an important

and rapid destruction even in the absence of local irritative

factors and occur in systemically healthy subjects. It has been

seen that particularly virulent bacteria trigger the process of bone

destruction in the disease, the main micro-organism involved is

Actinomycetemcomitans, which produces powerful leucotoxins that

can also severely damage the subject’s immune system cells. Some

clonal types of the bacterium are very pathogenic, and JP2 is always

isolated from subjects suffering from aggressive periodontitis

indicating that it is an important etiological agent. Regarding the

epidemiological aspects, the statistics show very variable data also

depending on the country, and so far the prevalence of aggressive

periodontitis is not known exactly but it can be said that it occurs

mainly in subjects of African descent and in individuals who are

predisposed from the genetic point of view.

To date there is no specific criterion for defining a high-risk

group for prepubertal pathology, and further research is needed to

identify a robust set of genetic, microbiological risk markers and

host factors that favor a diagnosis of the disease in association with

young people and adolescents. The identification of aggressive

periodontitis can be implemented through periodontal screening

associated with radiographs, and the routine use of BPE can be

helpful for early diagnosis. The treatment consists of the same

methods applied also to adult patients, that is to say a causal therapy,

a mechanic and a pharmacological one, in particular the studies

have shown that antibiotics associated with professional hygiene in

patients with aggressive periodontitis give very satisfactory results.

If, despite careful treatment and hygiene, a child continues to have

periodontal problems, it is necessary to investigate the general

health with more specific examinations. A form of periodontal

injury in a young person can also be a symptom of systemic diseases

that are extraneous to the parent’s awareness and early diagnosis

can become vitally important. Aggressive periodontitis, although

infrequent, is not to be underestimated and it is important to take

children to regular checkups and scaling sessions. Preventing and

diagnosing problems early is the key to success.

Read More Lupine Publishers

Pediatric Dentistry Journal Articles:

https://lupine-publishers-pediatric-dentistry.blogspot.com/