Lupine Publishers | Journal of Pediatric Dentistry

Abstract

Cleft lip is one of the most commonly encountered craniofacial deformities. The comprehensive treatment of cleft lip and palate deformities requires thoughtful consideration of the anatomic complexities of the deformity and the delicate balance between intervention and growth. As evidenced by the multiple techniques that have been developed for its repair, a functionally and aesthetically pleasing result is challenging to attain. In this study, we describe a modification of the surgical technique for the repair of complete unilateral cleft lip and palate, through the design of flag-shaped flaps without removing any tissue, as a modification to the rotation and advancement flaps or Millard technique.

Keywords: Cleft lip; cleft palate; rotation; advancement flap

Introduction

Since 390 B.C.E., the treatment of upper lip clefts has represented a challenge for surgeons [1]. The modern reconstruction of clefts requires an anatomical, functional, and tridimensional understanding of the cleft (and noncleft) lip, nose, and alveolar bone. Multiple repair techniques and modifications reflect the wide variety and constant evolution of the surgical principles for the repair of clefts [2]. Lip development occurs from the fourth to the seventh week of gestation [3,4]. Unilateral cleft lip occurs when the complete merging of the two maxillary processes and the medial nasal process on one side fails. Several anomalies can happen during the lip and palate development, finding the cleft lip and palate as the most frequent anomaly (and the cleft lip alone being less frequent) [5]. Cleft lip (with or without a cleft palate) is most frequently found in boys with a 6:3:1 ratio of left/ right/bilateral involvement, respectively [6]. This anomaly occurs in approximately 2 out of 1000 Asians, 1 out of 1000 Caucasians and 0.5 out of 1000 Afro-Americans. Cleft lip is usually isolated and associated with few syndromes like van der Woude, DiGeorge, Conotruncal anomaly, Velocardiofacial syndrome and Stickler [5]. The aim of this study is to describe a modification of the surgical technique for the nasal and complete unilateral cleft lip repair, with excellent aesthetical and functional results, without the need of removing any tissue

Technical Note

Preoperative consideration

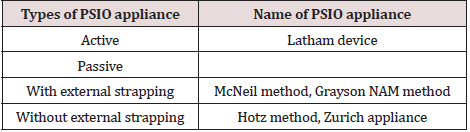

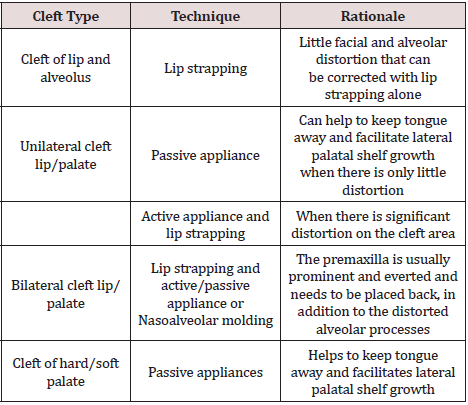

The ideal timing of lip repair is between 3 and 6 months of age and it is recommended that the patient weigh at least 10 pounds and have a hemoglobin of at least 10 g/dL. Prior to surgery, patients wear presurgical orthopedics. These techniques are ideally initiated in the first week of life and are continued until the time of repair. The technique proposed by Dr. Tulio Chacín, has been used exclusively to repair defects in a complete unilateral cleft lip and palate (CLP). This technique consists of rotation and advancement flaps with the modification of a flag-shaped flap design for the reconstruction of the posterior side of the lip and vestibule, tractioning the displaced alveolar process and repositioning the displaced nasal structures, without removing any tissue. The goal of cleft lip repair is to recreate a continuous oral sphincter, attain adequate vertical lip height with symmetry of cupid’s bow, and generate symmetry of the nostrils and nasal sill with a minimally visible scar. This study was approved by the Hospital Coromoto de Maracaibo IRB and all participants signed an informed consent agreement.

Surgical technique

Surgical repair is performed under general anesthesia with an oral tube placed at the midline lower lip so that it does not distort the upper lip. The neck is slightly ex- tended with a small shoulder roll and the OR table is tilted slightly in reverse Trendelenburg position. An alcohol pad is used to dry the vermillion boarder and enhance its identification. Key landmarks (as described below) are marked with methylene blue using a 30-gauge needle. This is performed prior to injection of the local anesthetic.

Landmarks

a) Point 1: Lateral peak of the lip (noncleft side).

b) Point 2: Center of the philtrum (located on the

mucocutaneous line).

c) Point 3: Lateral peak of the lip (cleft side) (equal to the

distance between 1-2).

d) Point 4: Lateral wall of the columellar base (noncleft side).

e) Point 5: Lateral wall of the columellar base (cleft side).

f) Point 6: Medial wall of the nasal ala (noncleft side).

g) Point 7: Medial wall of the nasal ala (cleft side). It’s drawn

from point 9 with a medial direction, equal to the distance

between 3-4.

h) Point 8: It is placed where the horizontal mucocutaneous

line becomes vertical and the mucous border starts to get thin

(the distance between 7-8 must be the same as the distance

between 3-5).

i) Point 9: Lateral wall of the nasal ala (cleft side).

j) Flap A: Lip mucosa of the noncleft side: used to reconstruct

the posterior wall of the lip, and it is fixated on the displaced

alveolar zone.

k) Flap B: Lip mucosa of the cleft side: used to reconstruct

the posterior wall of the lip, and it is fixated on the non-affected

alveolar ridge.

l) Point C: Used to release a portion of the incorrectly

positioned alar cartilage.

A – B = Flag-shaped flaps.

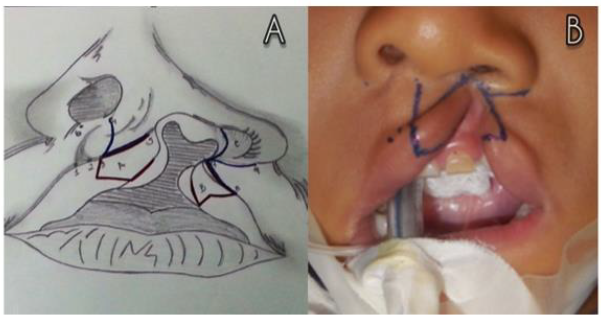

C = Nasal structural reposition (Figure 1).

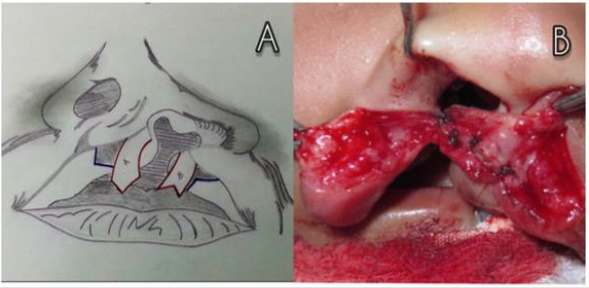

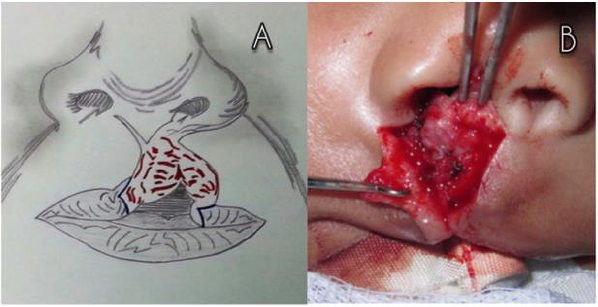

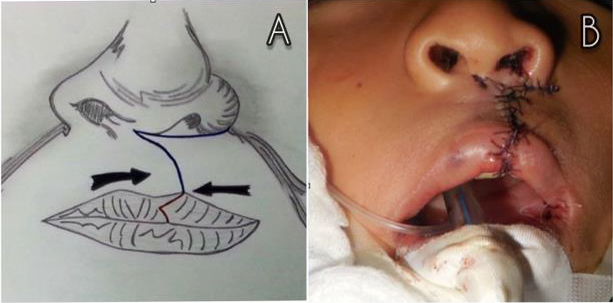

Taking into consideration these reference points and the principles of the rotation and advancement technique, the flagshaped flaps proposed by Dr. Tulio Chacín are designed. These flaps consist of an A flap on the lip vermillion of the noncleft side, having a triangular design with a distal end and a proximal base. A B flap on the contralateral vermillion, with an M form on its distal end and having a proximal base. Furthermore, a marginal incision is performed on the nasal vestibule of the cleft side in order to release the alar cartilage and improve the rotation of the nasal component. Once the design of the technique has been made, the nasal-labial reconstruction is conducted. Starting with the cephalic transposition of the flag shaped flaps, which are fixated on the nasal floor and the alveolar bone respectively, intertwining them (flap A with flap B), in order to create the posterior part of the lip and the oral vestibule as well as giving support to the nasal component (Figure 2). After that, the muscular and cutaneous component are settled (Figure 3). Additionally, on the remaining mucous plane, the coincidence of the triangular design on the lip vermillion is detailed, in order to break the wound and avoid its retraction, which could create a whistler deformity (Figure 4).

Discussion

The first record about unilateral cleft lip repair was written in

390 A.D. in the Tang dynasty in China. The edges of the cleft lip were

cut and sutured, and the child could not speak for a period of 100

days [7]. Ambroise Pare repaired unilateral cleft lips by merging/

joining both sides of the cleft, with a large needle and thread [8].

Rose and Thompson reported a modification, consisting of straightline

closures, for the unilateral cleft lip repair. All of these “straight

line” techniques closed the cleft. However, vertical retractions and

notches in the lip were frequently found after [9,10]. Several efforts

have been made in order to improve the aesthetic and functional

results obtained by the “straight line closure” technique. Within

these, several types of geometrical repairs with full-thickness

lip flaps are included. These techniques were designed with the

purpose of breaking the scars on the lip and to prevent vertical

retractions and notches [11]. LeMesurier reported a quadrangular

full thickness (with a lateral base) flap on the cleft side, which

intercepts the scar in the mucocutaneous union [12]. Tennison,

Marcks et al, introduced a triangular flap, where a Z-plasty was

designed on the inferior section of the lip [13,14]. Later, Randall

uses the same design as Tennison, but reducing the size of the

triangular flap [15]. Millard, in 1957, reports the rotation and

advancement flaps technique for the repair of the unilateral cleft

lip. This technique consists of 2 full-thickness flaps and its design

is made in order to place the scar on the philtral ridge, and it is the

most used technique to repair unilateral cleft lips nowadays [16].

The primary objective of the treatment of unilateral upper

lip clefts is to restore the anatomy and function of the lip. Other

objectives are to close the nasal floor, correct the asymmetry of the

nasal tip and to approximate the alveolar cleft. The rotation and

advancement technique involves two full-thickness flaps, which

are approached in order to repair the cleft and avoid the notching

of the lip. This design allows the rearrangement of the orbicularis

oris muscles. The geometrical flaps techniques require a more

accurate design, which allows creating flaps that are more precise

in shape and extent. This is ideal for less experienced surgeons.

However, with this technique the surgeon will have less flexibility

during the surgical procedure. The main advantage of the rotation

and advancement flaps is the flexibility of the technique, allowing

continuous modifications during its design, incisions and the repair.

Another advantage is that the incision is designed in order to place

the scar on the new philtral ridge. Most of the geometrical flaps

violate the philtral sub-unity. Within other advantages of the rotation

and advancement technique we can find: the minimum waste of

tissue and the maximum repair of the muscular component. One

disadvantage of this technique is that less experienced surgeons

could have difficulties with the flap design. Also, this technique

requires an extensive dissection, having the tendency to create a

small nostril on the cleft side. Because of this, the surgeon must try

to make the cleft side nostril slightly wider than the one from the

noncleft side, given the fact that it is easier to repair a wide nostril

than a narrow one [17].

In conclusion, the technique proposed by Dr. Tulio Chacín

for the nasal and complete unilateral cleft lip repair represents a

valuable tool for plastic/maxillofacial surgeons when repairing

this severe anomaly. Modifications in this technique include:

the reconstruction of the posterior wall of the lip, not removing

any tissue, the traction of the displaced alveolar process, the

reposition of the displaced nasal structures (giving them support),

and the breaking of the wound on the lip vermillion in order to

avoid retractions. The aesthetical and functional sequels of the

techniques used previously (such as: short and depressed lips, the

retraction of scars, an inadequate reposition of the affected nasal

ala and the collapse of the cleft alveolar process) create the need

for modifications, and some of them are obsolete and not even used

nowadays. We consider that the nasal and complete unilateral cleft

lip repair, using Dr. Tulio Chacín’s technique, may be one procedure

to choice during the correction of this complex anomaly.

Funding

No funding was received for this study

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

Special thanks to Michelle De Bacco for making the illustrations of the surgical technique.

Read More Lupine Publishers

Pediatric Dentistry Journal Articles:

https://lupine-publishers-pediatric-dentistry.blogspot.com/