Lupine Publishers | Journal of Pediatric Dentistry

Abstract

This case report describes the management strategies and the

evolution of the acute herpetic gingivostomatitis condition in

a 3-year-old female child with a focus on suppressing pain and to

improve oral intake with approaches to medicine and dentistry.

Keywords: Herpect Stomatitis; Drug Therapy; Child

Introduction

Herpetic gingivostomatitis is a condition that most often results

from initial gingiva (gums) and oral mucosa infection with herpes

simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1). While herpetic gingivostomatitis is

the most common cause of gingivostomatitis in children before the

age of 5, it can also occur in adults. The condition is characterized

by a prodrome of fever followed by an eruption of painful, ulcerative

lesions of the gingiva and mucosa, and often, yellow, perioral,

vesicular lesions. HSV-1 is usually spread from direct contact or

via droplets of oral secretions or lesions from an asymptomatic or

symptomatic individual. Once a patient is infected with the herpes

simplex virus, the infection can recur in the form of herpes labialis

with intermittent re-activation occurring throughout life [1]. The

pathogenesis of herpetic gingivostomatitis involves replication

of the herpes simplex virus, cell lysis, and eventual destruction

of mucosal tissue. Exposure to HSV-1 at abraded surfaces allows

the virus to enter and rapidly replicate in epidermal and dermal

cells. This results in the clinical manifestation of perioral blisters,

erosions of the lips and mucosa, and eventual hemorrhagic

crusting. Sufficient viral inoculation and replication allow the virus

to enter sensory and autonomic ganglia, where it travels intraaxonally to the ganglionic nerve bodies. HSV-1 most commonly

infects the trigeminal ganglia, where the virus remains latent

until reactivation most commonly in the form of herpes labialis

[2]. While most children with primary gingivostomatitis will

be asymptomatic, some will experience considerable pain and

discomfort and are at risk of dehydration. There are no large, well

designed studies to clearly determine appropriate therapy for all

children [3]. Professionals who treat children in this age group

must be able to diagnose and treat common oral manifestations

when necessary and should refer the child to a pediatrician for

effective treatment if the presence of any systemic alteration is

suspected [4]. Herpetic infections commonly affect the dental

profession’s anatomical area of responsibility and the diagnosis

and management of such infections fall in the purview of oral

healthcare providers. To administer competent care to patients

with herpetic infections, clinicians must understand the disease, its

treatment, the impact the disease or its treatment may have on the

patient and the extent to which the presence of a herpetic infection

may impact on caregivers in the clinical process [5]. The purpose

of this case report was to describe the treatment recommended for

a child diagnosed with acute herpetic gingivostomatitis associated

with tonsillitis and the ways to suppress pain and to improve oral

intake from the perspective of medicine and dentistry.

Case Report

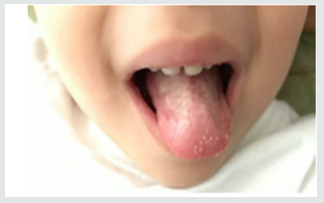

Parents of a 3-year-old and female child sought pediatrician

due to inflammation in the throat of their daughter, with fever and

irritability for two days, then their child feels pain in the mouth, and

the drooling starts with the appearance of diffuse lesions in the oral

mucosa, complaining of pain and having difficulty feeding. There

was the prescription of antibiotics (amoxicillin and clavulanate

potassium for oral suspension), anti-inflammatory and antipyretic.

Intraoral cleaning with gauze and saline was recommended and

the request for a new consultation, to eliminate the possibility of

fungal contamination. The diagnosis of acute and viral primary

herpetic gingivostomatitis was established (Figure 1). On intraoral

examination, gingiva appeared fiery red in color and multiple

vesicles were present on the attached mucosa. Multiple vesicles

and ulcers were seen along the lateral border and anterior surface

of the tongue. Both sided buccal mucosa revealed multiple vesicles.

Her parents also complained about his bad breath during this

period due to poor oral hygiene. Submandibular lymphatic glands

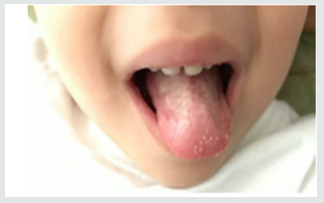

of the kid were enlarged [6]. The pediatric dentistry was consulted

because the child persisted with much pain, unable to sleep or eat

(Figure 2). There was then the option of laser applications, with

faster healing of ulcers and greater pain relief. There was substantial

improvement in food, oral hygiene and sleep. The patient will

perform control examinations, with simultaneous evaluation by

pediatrician and pediatric dentistry.

Figure 1: Child oral examination two days under antibiotic prescription.

Figure 2: Aspect of the child’s tongue on the fourth day of drug treatment.