Lupine Publishers | Journal of Pediatric Dentistry

Abstract

Bottle tooth decay is a common problem in dental medicine. Studies point to the relationship between mother’s knowledge and motivation to maintain oral hygiene and child’s oral health. The reason behind it is that mothers are usually the ones spending most of the time with the child during first years of life. The purpose of this study is to examine the level of pregnant women’s knowledge of the importance of primary teeth, caries and its causes, best time to begin tooth brushing and best time for first dental visit. In infant oral health lectures within the pregnancy class, 49 pregnant women were examined. The average age was 31, most of them were educated and employed. Before and after the lecture pregnant women got the same questionnaire and the results of the second questionnaire provides information on the importance of the lecture given within the course of pregnancy. Research results show that pregnant women consider primary teeth very important to childʹs development and general health. Most of them were aware that cleaning childʹs mouth starts even before the first primary tooth appearance and that primary teeth should be restored if necessary. Significant number of respondents knew the exact time of first tooth appearance. Knowledge of the recommended time for first dental visit and the caries risk factors was shown poor. The conclusion is that most pregnant women are unaware that breastfeeding, bottle feeding, using bedtime bottle and frequent feeding cause caries. Lecture on childʹs oral hygiene proved to be extremely useful because for most pregnant women that was the first time, they got that information.

Keywords: Pregnant women; bottle tooth decay; oral health knowledge; oral hygiene; prenatal care

Abbreviations:ECC: Early Childhood Caries; ADA: American Dental Association; ART: Atraumatic Restorative Treatment; EAPD: European Academy of Paediatric Dentistry; AAPD: American Academy of Paediatric Dentistry

Introduction

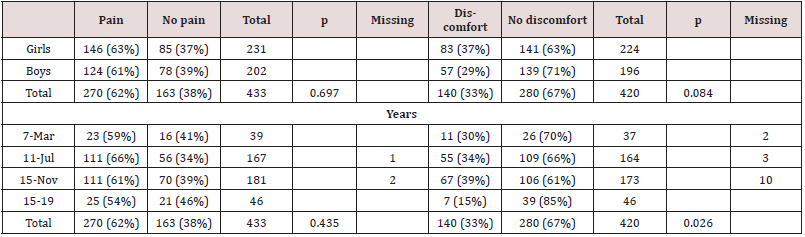

Early childhood caries (ECC) is a special type of tooth decay that occurs in children in the first three years of life [1]. The American Dental Association (ADA) defines ECC as the presence of one or more teeth affected by tooth decay, extracted teeth due to tooth decay and/or teeth provided with tooth filling in preschool children up to 71 months of age [2]. The reason why ECC is a separate clinical entity is the existence of a specific etiology of occurrence associated with breastfeeding and bottle feeding. Parents are often unaware of this, so they put their child to sleep with sweetened drinks, exposing the childʹs oral cavity to low pH throughout the night [3]. At night, the flow of saliva is greatly slowed down, which allows long-term retention of cariogenic solutions on the tooth surface, primarily upper milk incisors and canines [4]. Another reason why this type of tooth decay occurs is too frequent ad especially prolonged breastfeeding [5]. With the eruption of deciduous teeth, complex processes of demineralization and remineralization begin. Primary teeth are less resistant to tooth decay than permanent teeth due to poorer mineralization of enamel and consequently its tendency to wear out, thinner enamel and dentine and more voluminous pulp [1]. Research shows that the prevalence of bottle caries depends on the development of the country in which it is measured and on the criteria that are evaluated [6]. In developed countries that have good oral health programs, the prevalence of ECC is about 5%. Southeast European countries show a prevalence of about 20%, the Middle East 59%, and research results in North America vary from 11% to 72% [7]. Another study shows that the prevalence of bottle caries among preschool children in Zagreb is 30% (25% in girls and 48% in boys). The study was conducted on a sample of 145 children aged between 2 and 5 years. The results of the research showed that night feeding and feeding with sweetened drinks after first 24 months of life is the main risk factor for the development of ECC [8].

The clinical picture of ECC may vary depending on the frequency of feeding and oral hygiene. Depending on the number and location of teeth affected by caries, there is a mild type that involves isolated carious lesions on the incisors and / or molars of children aged 2 to 5 years. This is followed by a moderate type that affects the labial and palatal surfaces of the upper incisors with or without molar involvement and the absence of caries on the lower incisors. The severe type, also known as rampant caries, affects almost all teeth, including the lower incisors [9]. With the progression of caries, the first symptom appears, and that is pain. Pain when chewing can be the cause of a childʹs malnutrition and lack of nutrients. A link between ECC and childʹs slower physical development has been proven [10]. If left untreated, caries can progress to pulp and periapical disease, often resulting in tooth extraction. Premature extraction of deciduous teeth can have numerous consequences, from difficult chewing, impaired phonation, impaired aesthetics to orthodontic anomalies in the future. In addition, caries and early loss of deciduous teeth have an impact on the mental state of the child. The child experiences pain in the dental office early, which becomes a traumatic experience that often turns into anxiety. The approach to treatment depends on the severity of the clinical picture and the child’s cooperation. A good option for young and uncooperative children is the ART (atraumatic restorative treatment) program, which involves removing softened tooth tissue with chisels and excavators and filling with high-viscosity glass ionomer cement that releases fluoride and thus stops the spread of caries [1]. It is extremely important to start maintaining the oral hygiene of the child before his first baby teeth erupt. It is recommended to wrap a piece of gauze around the finger and pass it through the oral cavity after feeding. In this way, we not only remove food debris from the mouth, but also massage the alveolar ridge, which facilitates tooth eruption [11]. With the appearance of the first tooth in the oral cavity, most often the lower central incisor, brushing should begin. Cleaning the first teeth can also be done with gauze, and there are special toothbrushes for which it is indicated for which age they are suitable. The parent should consult a dentist which fluoride toothpaste is most suitable for his child’s age. The usual recommendation is from the European Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (EAPD). The concentration of fluoride in pastes suitable for children aged 6 months to 2 years is 500 ppm, for children aged 2 to 6 years 500-1000 ppm, and for children older than 6 years the amount of 1000-1450 ppm corresponds [12]. In addition to proper oral hygiene, proper nutrition of the child is also important. It is desirable to limit the frequency of feeding the child to 5-6 times a day. There should be a period of at least 3 hours between meals in which only water is allowed to be consumed. In this way, the saliva buffer mechanism neutralizes acids and mechanically flushes food debris from the oral cavity further into the digestive system [12]. The most common mistakes parents make, resulting in bottle caries, are putting the child to sleep with sugary drinks, holding the child to the chest after falling asleep, feeding at night, and allowing the child to walk with the bottle drinking its contents little by little [2]. Parents’ ignorance of the importance of proper and regular maintenance of a child’s oral hygiene is the cause of their lack of motivation to maintain it, which results in caries. The recommended time for the first visit to the dentist according to the AAPD (American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry) is from 6 months to a year or from the eruption of the first tooth to a year. The caries risk is assessed by talking to the child’s parent about his eating habits, oral hygiene, and the habits of the parents themselves. The aim of this research is to find out the level of knowledge about the oral health of the child of future parents, especially mothers who most often take care of the child in the first months of life. Lowereducated mothers and unemployed mothers are expected to have a lower level of knowledge about maintaining a child’s oral health.

Materials and Methods

In this research, the participants of the course for pregnant women held at the Clinic for Gynecology and Obstetrics, more precisely, the participants of the lecture “Care for the health and care of the child’s teeth in pregnancy and infancy” were examined. The research was conducted in the form of a questionnaire (Appendix 1), which was distributed to all participants at the beginning of the lecture, and which was completed by pregnant women before the beginning of the lecture. The same questionnaire, but without data on socio-economic status, was distributed and completed after the lecture. The questionnaire was designed at the Department of Pediatric Dentistry Study of Dental Medicine and consists of two groups of questions. The first group of questions focuses on the knowledge of pregnant women about maintaining oral hygiene of the child, caries, the importance of milk dentition and the recommended age of the child to start brushing teeth and the first visit to the dentist. The questions are in the form of adding, rounding YES-NO to the claims about oral hygiene, and in the form of rounding the statements that are closest to their opinion about caries, from “not at all” to “completely yes”. The second group of questions refers to the marital status, level of education, employment and occupation of the pregnant woman and the father of the child. Round off YES or NO to the question on employment and state the occupation, type of work and institutions where the pregnant woman and the child’s father work. Finally, data on family size and number of children in the family are filled out.

Results

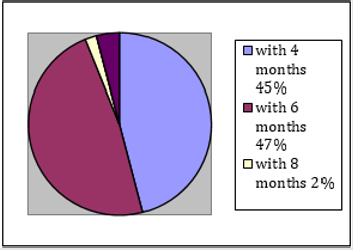

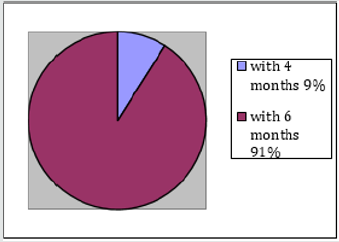

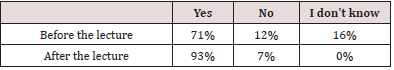

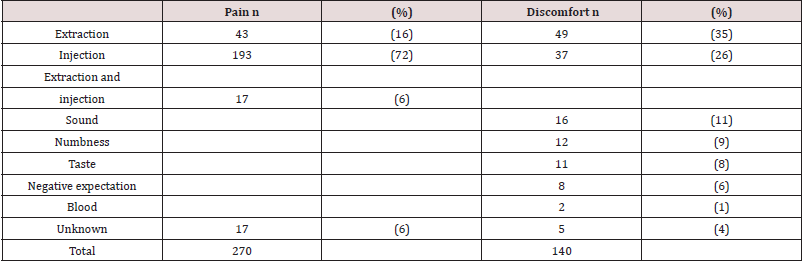

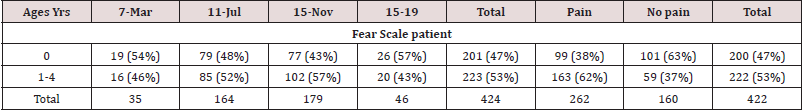

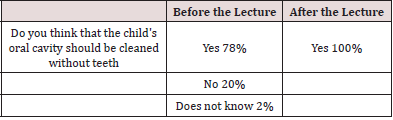

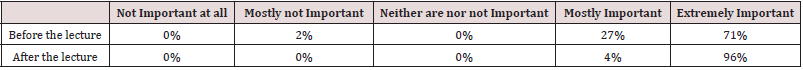

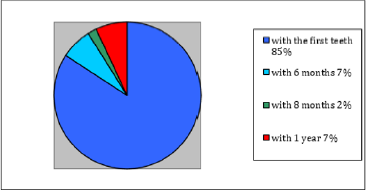

49 pregnant women with an average age of 31 participated in this study. The majority (61%) of pregnant women are married, have a university degree (67%) and are employed (87%). Fathers are mostly university educated (43%) or have completed vocational school (43%), and 98% are employed. The vast majority of respondents (92%) have this first child, and 71% claim that this is the first course for pregnant women attending and that they have never received information on maintaining oral hygiene (92%). The survey showed that most pregnant women know that oral hygiene must be maintained while the baby is still toothless. During the lecture, attention was once again drawn to the importance of cleaning the mouth of a child without teeth and the way in which this is done was described. All pregnant women answered in the affirmative after the lecture (Table 1). The next issue was the age of the baby in the months when the first baby teeth begin to erupt. The offered answers were 4, 6, 8, 10 and 12 months. Before the lecture, 47% of pregnant women answered for 6 months, and after the lecture, 91% answered for 6 months (Graphs 1 & 2). Pregnant women were aware even before the lecture that baby teeth were important for the baby. As many as 71% of respondents answered that deciduous teeth are extremely important, while 27% answered that they are mostly important. After the lecture, 96% of respondents claim that deciduous teeth are extremely important (Table 2). The next question was answered by overwriting, so there is a whole range of answers that needed to be sorted into correct or incorrect. The correct answer was considered to be all those who indicated that teeth should be brushed as soon as possible, when the first teeth erupt. Answers of the “2 months” and “3 months” types were also considered correct under the assumption that the respondents meant toothless oral hygiene which continued and dental hygiene when they erupted. Any responses that suggest brushing your teeth from 1 year onwards are considered guilty.

Table 1: Answers to the question on maintaining the hygiene of child’s oral cavity without teeth, before and after the lecture.

Table 2: Opinion of pregnant women on the importance of deciduous teeth for the child, before and after the lecture.

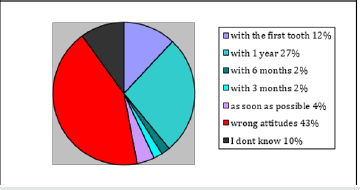

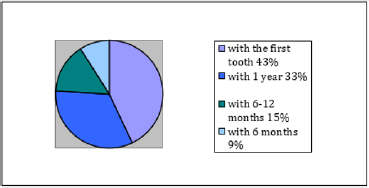

Before the lecture, 67% of respondents answered with one of the correct answers, and after the lecture 93% (Graphs 3 & 4). The next question was also answered by adding. Due to the large number of different incorrect answers, it is impossible to make a clear picture of the attitudes of pregnant women on this issue, so all the wrong attitudes will be classified into a single group. Some of the wrong attitudes were: “when we notice a defect”, “when all the teeth grow”, “when the first tooth falls out”, “at the age of 2” and many others. The correct attitude is considered to be all those who indicate the first visit to the dentist as early as 1 year of age. Before the lecture, 47% of pregnant women had the correct attitude about the time of the first examination, and after the lecture, all respondents (100%) had the correct attitude (Graphs 5 & 6).

Graph 3: Opinion of pregnant women about the time of the beginning of brushing the child’s teeth before the lecture.

Graph 4: Opinion of pregnant women about the time of the beginning of brushing the child’s teeth after the lecture.

Graph 5: Attitudes of pregnant women about the time of the first visit to the dentist before the lecture.

Graph 6: Attitudes of pregnant women about the time of the first visit to the dentist after the lecture.

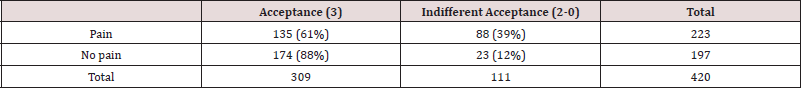

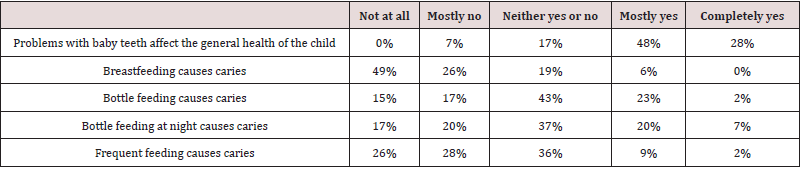

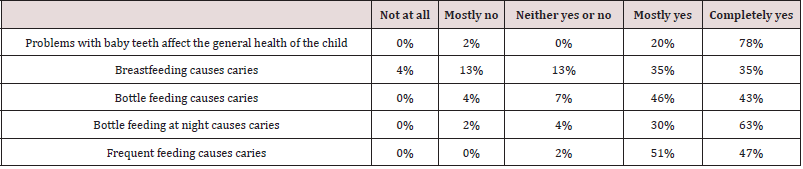

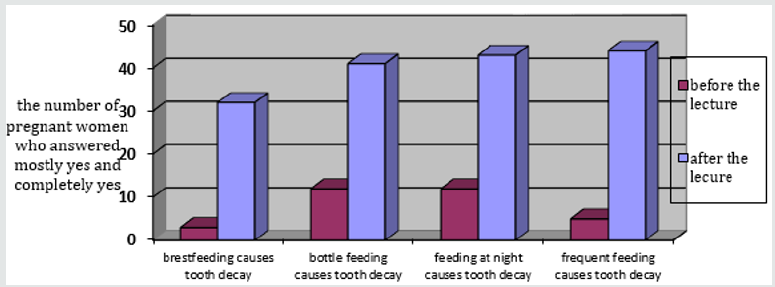

To the question „Are deciduous teeth being repaired“, 71% of respondents circled the answer YES before the lecture. After the lecture, 93% of respondents answered YES (Table 3). The next group of questions examines the attitudes of pregnant women about the causes of caries. With each statement, it was necessary to round off the position most similar to the position of the respondent, from “not at all” to “completely yes”. In this group of questions, pregnant women had the worst results (Table 4). Pregnant women’s knowledge of the causes of caries has greatly improved after the lecture (Table 5 and Graph 7).

Table 4:Attitudes of pregnant women about the impact of deciduous teeth on general health and factors for the development of caries before lectures.

Table 5: Attitudes of pregnant women about the impact of deciduous teeth on general health and factors for the development of caries after lectures.

Graph 7: Attitudes of pregnant women about risk factors that cause caries before and after the lectures.

Discussion

Most of the respondents were not previously advised on maintaining the child’s oral hygiene. Nevertheless, this research has shown that pregnant women consider deciduous teeth important for the development and general condition of the baby. This figure coincides with the results of a study in Nigeria in which 79.2% of pregnant women stated that baby teeth are important for a child. However, pregnant women who participated in this study showed better knowledge regarding the repair of deciduous teeth (71% answered that they are being repaired) than pregnant women who participated in the study in Nigeria (43.6% did not know if deciduous teeth were being repaired) [13]. Most correctly answered the question about cleaning the oral cavity without teeth and the question about the time of eruption of the first teeth. Two descriptive questions about the time of the beginning of brushing and the first visit to the dentist have worse results, but half of the respondents answered these questions correctly. A similar study has been conducted in Germany among midwives. Midwives were asked questions about the advice they give to young mothers and pregnant women. Most claim to advise pregnant women about early childhood caries, but when asked about their first visit to the dentist, only 9% responded within the first year of life. Similar to the results of this research, 60% of midwives recommend starting brushing when the first tooth erupts [14]. A study conducted in India showed a poorer level of knowledge of pregnant women and young mothers about the time of the first visit to the dentist. Only 22.3% of pregnant women answered that the first visit to the dentist must be around the period of the eruption of the first teeth, while this research showed that about 47% of pregnant women have the correct attitude. The reason for this is because it is very likely the degree of illiteracy among women in India [15]. The area from which pregnant women showed the least knowledge is the development of caries. Specifically, they were unaware of the risky behaviors that lead to caries. 49% of respondents answered that breastfeeding does not cause caries at all, probably because they can hardly associate breastfeeding as a physiological action with negative consequences. A similar degree of ignorance of pregnant women is shown by questions about bottle-feeding, bottle-sleeping, and frequent feeding. Research has shown that pregnant women do not have sufficient knowledge of risky behaviors for caries, so they do not have the necessary knowledge to prevent caries in their child. The lecture on oral care for children as part of a course for pregnant women was the first encounter for most pregnant women with information on the causes of caries, harmful habits, tips for maintaining oral hygiene, the time to start brushing and the first visit to the dentist. Since the same but abbreviated survey was completed after the lecture, it is easy to notice an improvement in the knowledge of the mentioned topics, which supports the importance of timely education of young mothers on maintaining oral hygiene of the child.

Conclusions

This research showed that the participants in the course for pregnant women at the Clinic for Gynecology and Obstetrics in Rijeka do not have satisfactory knowledge about the oral health of the child, primarily about the risky behavior for early childhood caries. Most pregnant women were not aware that breastfeeding, bottle feeding and sleeping and frequent feeding cause tooth decay. More than half of pregnant women were of the opinion that the child should be taken to the dentist for the first visit at the age later than recommended (until the age of 1) or did not know the answer. For most pregnant women, the mentioned lecture was the first encounter with information on maintaining the oral health of the child. After the lecture, pregnant women had a much better knowledge of caries and all other issues, which indicates the importance of the mentioned lecture as part of the course for pregnant women.

Read More Lupine Publishers

Pediatric Dentistry Journal Articles:

https://lupine-publishers-pediatric-dentistry.blogspot.com/