Lupine Publishers | Journal of Pediatric Dentistry

Abstract

Introduction: Children’s reports of experiences from dental invasive procedures are scarce. The aim was to renew and actualize the understanding of children’s experiences of pain, discomfort, fear, and cooperation during the dental extraction procedures. A further aim was to study the frequency of parental presence during dental extractions.

Methods: The study was based on a sample of children and adolescents aged 3–19 years in the Region Västra Götaland (RVG) and Region Örebro County (ROC). It was a 5-year cohort study of an accelerated longitudinal design, named BITA (Barn I TAndvården = Children in dental care). Data on children’s pain, discomfort, fear, cooperation, and parental presence were assessed and compiled.

Results: 2363 out of 3134 children in the four age cohorts became eligible for inclusion. The cohorts included Cohort 1 (3-7 years old; n=695 children), Cohort 2 (7-11 years old; n=642 children), Cohort 3 (11-15 years old; n=574 children), and Cohort 4 (15-19 years old; n=452 children). There were 1215 girls (51%) and 1148 boys (49%). Extractions were assessed as painful by 62%. Discomfort was reported by 33%. Dental fear was reported by 47%. During painful extractions, no fear was reported by 38%, while in painless extractions, no fear was reported by 63%. Dental fear was most common in the age group 11-15 years. Full treatment acceptance was recorded in 73.6% during the extractions. In extractions reported to cause pain, 61% cooperated well. Most of the patients (77%) showed full treatment acceptance with parental presence in the dental room. The corresponding figure was 55% for the parent not being present.

Conclusion: Dental extractions continue to constitute one of the most complex and challenging treatment situations for the young patient. The oral injection was most frequently reported to cause pain, discomfort, and fear during dental extractions. Dentists should make efforts to prevent pain and discomfort, as well as utilize parental support for the child’s sense of security during dental extractions.

Keywords: Paediatric; pain management; pain assessment; clinical procedures

Abbreviations: RVG: Region Västra Götaland, ROC: Region Örebro County; BITA: Barn I T Andvården; DFA: Dental Fear and Anxiety; BMP: Behavior Management Problems

Introduction

Invasive dental treatments such as anesthesia and extractions have shown to stress children and adolescents the most [1,2]. In a study performed on 368 Swedish children and adolescents (8- 19 years), the prevailing reported painful dental procedures were injection, tooth extraction, drilling and performing a filling [1]. Negative treatment experiences may trigger a vicious cycle, i.e., leading to avoidance of dental appointments and hindering more positive experiences to take place [3-5]. Furthermore, avoiding dental appointments may affect the oral health [3-5] jeopardizing the well-being of young patients with long-term consequences [3-5]. Less traumatizing methods for invasive dental techniques during injection and extraction are available, although to date, studies report that the usage of pain preventive interventions such as topical anesthesia, local anesthesia, or analgesics are still substandard [6-8]. The routines applied by Swedish dentists have shown that ‘about 35% were more indifferent to their patient’s experiences of pain and psychological management’ [7]. Apart from pain experiences, invasive and/or noninvasive dental procedures may cause children discomfort. Although there is no universally prevailing definition, the phenomenon might be explained as psychological or bodily distress or annoyance, i.e., anything that disturbs the well-being [9]. Children’s experience of discomfort in dentistry has previously not been given much attention. Invasive procedures also test dentists’ technical skills with a need to be knowledgeable on children’s developmental levels, contemporary psychology, and pedagogical interactions. Furthermore, dentists may face difficulties in the interaction with the child/parent dyad [10].

Parental attitudes and behavior have been suggested to either facilitate or undermine the child’s cooperation and thus affect the treatment outcome [11-14]. It could be hypothesized that some dentists consider parents a hindrance, therefore not inviting them into the dental room. Seen from the young patients’ standpoint, such an approach may be controversial as parental absence may diminish the perception of security, predisposing to fear, pain, and discomfort experiences [14]. In Sweden, a prevailing tradition and the Dental Act have allowed parents to support their children in medical and dental settings [15]. The practice has thus become a norm in the pediatric dental community, despite alternative behavior management techniques [16]. At present, there is insufficient knowledge in the area of children’s and adolescents’ experience of invasive procedures, and dentists’ attitudes and praxis towards these. Furthermore, there is a lack of knowledge on how general dentists understand the parental interaction and how frequently they make use of parental help during extractions. The aim was to renew and actualize the understanding of children’s experiences of pain, discomfort, fear, and cooperation during dental extraction procedures. A further aim was to study the frequency of parental presence during dental extractions.

Patients and Methods

Patients

This study was based on a representative sample of children and adolescents aged 3–19 years in the Region Västra Götaland (RVG) and Region Örebro County (ROC). The project was a 5-year cohort study of an accelerated longitudinal design, named BITA (Barn I TAndvården = Children in dental care). It concerned different aspects of children in the dental situation when attending regular general dentistry. Four age cohorts with children aged 3, 7, 11 and 15 years, from seven Public Dental Service clinics in RVG and five in ROC, were invited to participate and then followed over a 5-year period in conjunction with regular dental visits. The clinics were selected to reflect the respective populations and to cover urban and rural areas. A total of 3134 children were considered for the study.

Procedure

Clinical registrations

The children’s ordinary dentists registered all performed dental treatments after each session. For this study, extraction treatments were selected, and assessments and self-ratings were made and registered.

Self-reported pain

Each child made a self-assessment of pain experienced after the extraction. The child was asked the question: Was anything painful? Yes or no? If the child answered yes, the pain intensity was measured using a visual analog scale (VAS) consisting of 11 points running from 0 = no pain, to 10 = worst pain possible. Parallel to the scale, six faces express different levels of pain/distress where young children point out the face matching their level of pain. Furthermore, the child was asked the question: What was painful?

Self-reported discomfort

The child was asked the question: Did anything cause discomfort? Yes or no? If the child answered yes, the discomfort was measured using a visual rating scale (VRS) consisting of 11 points running from 0 = no discomfort, to 10 = worst discomfort possible. Parallel to the scale, six faces express different levels of discomfort where young children point out the face matching their level of discomfort. Furthermore, the child was asked the question: What caused the discomfort?

Self-reported fear

Children assessed their fear at the dental treatment by answering the question, how did you feel today? The alternative answers were Not afraid at all = 0 or Afraid, on a scale graded 1-4.

Assessment of the child’s cooperation

The child´s cooperation was graded by the treating dental personnel according to the scale by Rud and Kisling, rated 3 to 0, where 3= full acceptance to treatment; 2= indifferent acceptance; 1= reluctant acceptance; and 0= non-acceptance.

Parental presence

Parental presence in the dental room was documented.

Ethics

The application for ethical review (No. 286-07) was approved.

Statistical methods

In addition to descriptive statistics in terms of frequency distributions, means, and standard deviations, differences between genders and between cohorts were analyzed using Chi-square tests. The statistical analyses were performed in IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 23.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA ) and p values below 0.05 represented statistical significance.

Results

3134 children were invited to participate in the study; 771 declined participation, whereby 2363 children in the four age cohorts became eligible for inclusion. These four age cohorts included Cohort 1 (born 2005; from 3-7 years old during the study period; n=695 children, 3906 visits), Cohort 2 (born 2001; 7-11 years old; n=642 children, 4588 visits), Cohort 3 (born 1997; 11-15 years old; n=574 children, 4085 visits), and Cohort 4 (born 1993; 15-19 years old; n=452 children, 3315 visits). The distribution between the genders was 1215 girls (51%) and 1148 boys (49%).

Pain and discomfort during extractions

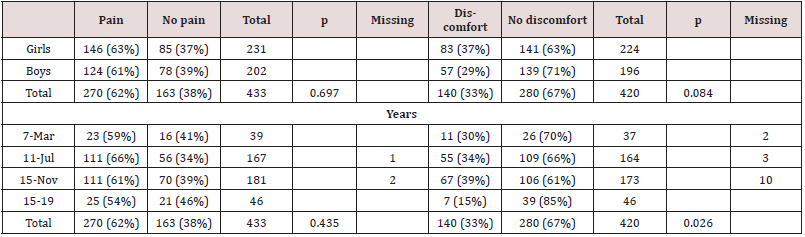

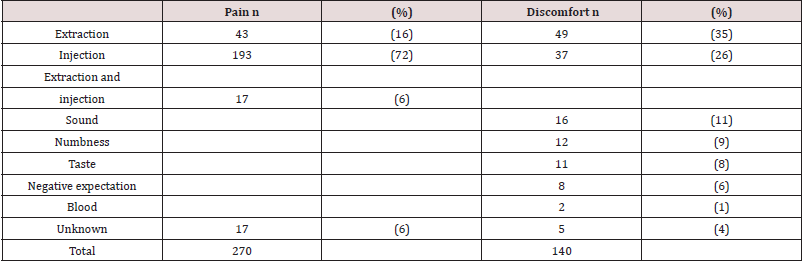

Extractions were assessed as painful by 62% (Table 1). The reasons were the extraction itself (16%), the injection (72%) or the combination of injection and extraction procedures (6%) (Table 2). Discomfort was reported in 33% of the extractions (Table 1). The reasons for discomfort pointed to the extraction per se (37%), followed by injection (26%) (Table 2). No statistically significant difference between the genders or cohorts was found regarding the experience of pain. There was a statistically significant difference between cohorts, with the lowest proportion of discomfort stated by the oldest group (30%, 34%, 39%, 15%; p=0.026) (Table 1). Primary (n=323) and permanent (n=102) tooth extractions were assessed as painful in equal proportions (63% and 61%), while discomfort was slightly less often reported for primary teeth, compared to permanent tooth extractions (32% and 37%). 11 tooth extractions lacked complete documentation. Topical anesthesia was applied in 35%, with no statistically significant difference between application and no application regarding the reported experience of pain and/or discomfort. Conscious sedation drugs were used in 6%.

Table 1: Extraction appointments (n=436 extractions) and the young patients’, reports of pain and discomfort in adjunction to the treatment, related to gender and age-cohorts.

Chi-2 test, P probability value

Table 2: Children’s reported reasons for pain (n=270) and discomfort (n=140) in connection to the extraction procedures.

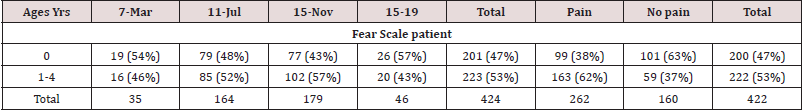

Dental fear and pain during extractions

Children’s self-assessment of dental fear resulted in 47% reporting no dental fear in conjunction with the extractions. During painful extractions, no fear was reported by 38%, while in painless extractions, no fear was reported by 63% (Table 3). Dental fear was most common in the age group 11-15 years, followed by the age group 7-11 years (Table 3). No statistically significant difference between the genders or cohorts was found regarding the experience of pain. There was a statistically significant difference between cohorts, with the lowest proportion of discomfort stated by the oldest group (30%, 34%, 39%, 15%; p=0.026) (Table 1). Primary (n=323) and permanent (n=102) tooth extractions were assessed as painful in equal proportions (63% and 61%), while discomfort was slightly less often reported for primary teeth, compared to permanent tooth extractions (32% and 37%). 11 tooth extractions lacked complete documentation. Topical anesthesia was applied in 35%, with no statistically significant difference between application and no application regarding the reported experience of pain and/ or discomfort. Conscious sedation drugs were used in 6%.

Table 3:Young patients’ (age cohorts) self-rated dental fear and pain experiences. The subjective assessment of pain=Yes or No was given after the extraction procedure (missing data n=14). Dental fear, as rated on a scale 0 to 4, 0=no fear, fear =1-4, (missing data n=12).

Dental fear and pain during extractions Children’s self-assessment of dental fear resulted in 47% reporting no dental fear in conjunction with the extractions. During painful extractions, no fear was reported by 38%, while in painless extractions, no fear was reported by 63% (Table 3). Dental fear was most common in the age group 11-15 years, followed by the age group 7-11 years (Table 3).

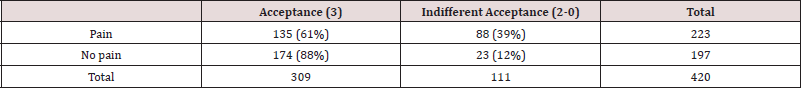

The child´s cooperation while experiencing pain

Full treatment acceptance was recorded in 73.6% during the extractions. In extractions reported to cause pain, 61% cooperated well (Table 4).

Table 4: Children’s self-rated pain experiences and the degree of treatment acceptance, as rated by the dental personnel, on a scale 3-0, by Rud and Kisling.

The subjective assessment of pain=Yes or No was given by the child after the extraction (missing data n=16).

Treatment acceptance during parental presence

Most of the patients (77%) showed full treatment acceptance with parental presence in the dental room. The corresponding figure was 55% for the parent not being present. All 37 three-yearold had their parents present in the dental room. Among the 166 seven-year-olds, two were not accompanied by an adult. Among the 11-year-olds, 26 out of 179 had no parent present. Among the 15-year-olds, 25 out of 45 managed on their own.

Discussion

This longitudinal, 5-year study voiced children’s and adolescents’ self-reported pain, discomfort, and fear during dental extractions. The main results showed that more than 60% of the dental extraction appointments involved painful experiences. Furthermore, pain was equally reported among the different age groups. The extracted teeth were predominantly performed in young schoolchildren. This may indicate that more vulnerable children were at risk experiencing pain at an early stage of their dental care encounters. Within the extraction procedure, the injection was most frequently reported responsible for the negative experiences. During decades, pain has been connected with dental extractions and concerned children and adolescents [17]. It could be reasoned that the injection techniques have not developed sufficiently, despite alternative anesthesia delivery methods, Computer controlled local anesthesia, Jet injectors, Iontophoresis and Computer controlled intraosseous anesthesia [18,19]. An explanation might be that as these methods lie in the hands of numerous dentists, the injection performance may not be possible to calibrate. Other factors adding to the child’s pain experience may be the dentists handling the onset of the anesthetic, the amount of delivered anesthesia, or a complementary anesthesia differently. A noteworthy result was that topical anesthesia was applied in only 35% by the dentists, which is astonishingly low given the scientific evidence in support of the technique, which is in alignment with earlier result [7]. Furthermore, adding to the children’s uneasiness, discomfort was reported frequently during the extraction procedure. Thus, despite a complete anesthesia numbness, discomfort may have been experienced due to cracking sounds and/or the perceived pressure during the dental luxation. Discomfort has not been given much attention in the dental literature compared to general medical care [20]. The frequently reported discomfort also suggest that the dentists may not have practiced current theoretical knowledge sufficiently, which needs to be recognized [7,8].

No studies among dentists have confirmed the Knowledge

Transition to have improved regarding dental invasive procedures

in general or oral anesthesia specifically [21,22]. An explanation

may be the complex interaction between the applied injection

technique and the dentist’s way of psychological and pedagogical

coaching [23-25]. Preferably, children should beforehand be

prepared on anesthesia numbness sensation, luxation cracking

sounds, increasing tissue-pressure during luxation, postoperative

taste-sensation (iron, i.e., blood), and the subsequent inconvenience

of not being able to enjoy a meal directly after the tooth extraction.

Studies on Dental Fear and Anxiety (DFA) have showed that invasive

dental procedures, such as extractions and injections, were by many

children and adolescents associated with fear and anxiety [26,27].

In the current study, 47% of the extraction appointments were

experienced without fear. From this perspective, the extractions

were performed under satisfactory conditions. On the other hand,

53% of the children experienced fear, ranging from a bit nervous

to terrified. Versloot et al. (2008) have reasoned that the level of

dental anxiety may be of greater importance for the child’s reaction

than the injection technique itself [27]. Given that young patients’

early pain encounters may not only trigger. Behavior Management

Problems (BMP) and/or Dental Fear and Anxiety (DFA), but may

also alter future pain responses, the results of this study are notable

[28]. Contrary to the pain reports that were equally common in all

age cohorts of the current study, DFA was more frequently reported

in schoolchildren. This may define a vulnerable developmental

stage, requiring parental presence and support. The relatively high

proportion of extraction appointments performed with the parent

does not present in the room calls for additional studies.

The current study presented that parental presence in the dental

room was most frequent among children 3-12 years old, hereafter

the presence significantly declined. Praxis has suggested that most

parents are experts on their child’s behavior and reactions. Perets

and Zadick (1998) found that most parents would assist, should

the dentist not succeed to manage their child [29]. Vasiliki (2016)

also stated that children responded more positively in the dental

room with parental presence [11]. Pfefferle et al. (1982) reasoned

that this may be due to parents knowing their child’s reactions

and capabilities in challenging situations [30]. The current study

demonstrated that most children cooperated fully during the dental

extraction procedures despite experiencing discomfort or pain. A

possible interpretation is that these children were not equipped

to speak their needs, or they surrendered easily to authorities.

Indirectly, the results also suggested that dentists practiced varied

theoretical understanding, technical skills, and ethical attitudes

during dental extraction procedures, not always in favor of the

child. A limitation of this study may be argued that children below

six years of age were not reliable to give accurate assessments

of their experiences. However, there is a strong opinion among

researchers that children from the age of 3-4 years are capable to

communicate well and should be supported to express perceptions

of discomfort and pain [31]. The strength of this study was that the

results originated from a 5-year longitudinal perspective based

on young patients’ experiences from the extraction appointments.

These results, regarding pain, discomfort and DFA, have not been

contradicted in the recent literature and are valuable for clinical

discussions. In conclusion, dental extractions continue to constitute

one of the utmost intricate and challenging treatment situations for

young patients. The oral injection was most frequently reported to

cause pain, discomfort, and fear during dental extractions. Dentists

should make efforts to prevent pain and discomfort, as well as

utilize parental support for the child’s sense of security during

dental extractions.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the Public Dental Service, Region Västra Götaland and Region Örebro County, Sweden.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Read More Lupine Publishers

Pediatric Dentistry Journal Articles:

https://lupine-publishers-pediatric-dentistry.blogspot.com/

No comments:

Post a Comment